Law campaign

Handloom laws to empower the Tantis

S. M. Masum Billah

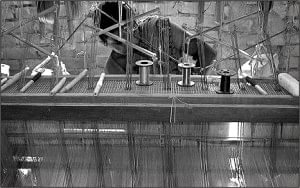

THE weavers are a community preserving the handloom heritage of Bangladesh. They propels a handsome portion of national economy, retains the signifier of native culture, either ethnic or Bengalee. But this industry, the pivotal source of cloth supply to the teeming millions of Bangladesh from time immemorial, is now on the brink of extinction. The Bangladesh Handloom Census Report 2003 reveals that the operational looms in 1990 were 347214 while it reduced to 31185 in 2003. This is certainly not an encouraging picture. The economic depression & natural calamity has added a fuel to the situation culminating hundreds of looms in-operational.

THE weavers are a community preserving the handloom heritage of Bangladesh. They propels a handsome portion of national economy, retains the signifier of native culture, either ethnic or Bengalee. But this industry, the pivotal source of cloth supply to the teeming millions of Bangladesh from time immemorial, is now on the brink of extinction. The Bangladesh Handloom Census Report 2003 reveals that the operational looms in 1990 were 347214 while it reduced to 31185 in 2003. This is certainly not an encouraging picture. The economic depression & natural calamity has added a fuel to the situation culminating hundreds of looms in-operational.

Inefficient administration by the government machinery and their lack of foresightedness, among other things, not only contributed to the failure of the policies but also complicated the situation. The threshold of globalization has posed a serious threat to the tant industry. Arguably, it deserves special concentration in terms of policy formulation, law making and community development.

Bangladesh Handloom Board Ordinance, 1977 defines handloom as “a weaving device operated manually for production of fabrics other than 100% silk or art silk and includes the following types of looms falling outside the scope of the Factories Act, 1965 a. Shuttle pit loom including carpet loom and tape loom b. Fly shuttle pit loom c. Fly shuttle pit loom d. Semi-automatic of Chittaranjon loom e. Hattersley's loom f. Special types loom used by tribal people g. Cottage loom that is power loom up to three unit located in household and driven by power f. any other loom which is operated in household for production of heavy or light fabrics.” The definition apparently engulfs wider amplitude no doubt. But the definition needs to be revisited in the changing circumstances.

Bangladesh Handloom Board (Amendment) Act 1990 in its justification paragraph had stated that the handloom industry is providing 63% of the clothing produce in the country. However, some recent newspaper study discloses that this contribution has shrunk to 43% over the years. About 15 lakh people (9 lakh as per New Nation report of September, 2007) directly or indirectly are engaged in this sector. Distributive justice has been an utter failure in case of impoverished Tanti community as a whole, as because from 1990, a considerable time has elapsed exhibiting a tremendous transformation in economic life of the Tantis. A process of structural dualism can be found in regulating the sector. It is held captive by a class of exploitative intermediaries, who left little surplus to the weavers for upgrading Tant technology.

The presence of such 'exploitative intermediaries' contradicts the constitutional oath of founding a society 'free from exploitation'. Growth of the handloom industry is now under threat particularly from a reactivated power loom industry and the rampant growth of smuggled fabrics from India is driving the industry as a whole to the point of attrition. While urge from different segments of the society to rescue the Tantis from being impoverished has remained largely a 'rhetorical protestation', it is submitted that a revitalization and renewed vigor is needed to expose the threshold of the problems in this sector.

Newspaper report exposes a very discouraging picture of the hand loom sector of Narshingdi, for example. Once known as a Manchester of Bangladesh for its handloom textiles, Narshingdi district is going through a very difficult phase. About 70 percent of the handlooms are closed there. Over the past thirty-five years, one lakh looms have closed down in this district and around 80,000 weavers lost their employment.

The grievances of this type of subjugated and browbeaten community is well protected and secluded by our constitution. The constitution of Bangladesh contemplates economic democracy as a fundamental aim of the state. It vows to realize a society where rule of law, fundamental human rights and freedom, equality and justice economic, political and social-- will be secured for all citizens. It also pledges that all citizens are equal before law and are entitled to equal protection of law. A complete depiction of republico concept is enshrined within the ambit of constitution where it is written that all power belongs to the people. Empowerment of the mass people is the sine qua non in order to see that this power is effectively exercised. 'Empowerment' as the term connotes in modern terminology, predominantly involves economic dimension. So, for the purpose of attaining constitutional pledge of 'social justice' in the meaning of economic democracy, it is incumbent that all communities of the country are allowed to flourish in terms of their life, livelihood, economic and cultural enrichment.

Article 14 of the Bangladesh Constitution casts responsibility upon the sate to 'emancipate the toiling masses' from all forms of exploitation. Article 16 ordains to adopt effective measures to bring about a radical transformation in the rural areas through, amongst others, the 'development of cottage and other industries' and to remove disparity in the standards of living among urban and rural areas progressively. Guaranteeing endeavor to ensure equality of opportunity for every citizens, the assertion of Article 19 of the constitution has also become unequivocal and poignant. It stipulates that state shall adopt effective measures to remove social and economic inequality among citizens and ensure opportunities in order to attain a uniform level of economic development throughout the Republic. Article 23 ordains to take measures to conserve the cultural traditions and heritage of the people to foster and improve the arts of all sections of people for their participation in the enrichment of national culture. These all flourishments of a welfare state has transformed into economic, social and cultural rights of the citizens. With the ripeness of inalienability, indivisibility, universality and interrelatedness of human rights concept, the watershed between civil & political rights (i.e. justiciable rights) on the one hand, and economic, social & cultural rights (non-justiciable) on the other hand, have become too meager.

It is in this background the problem of the handloom sector and the weavers of Bangladesh should be viewed and addressed. For ensuring community empowerment the present status of handloom sector, its stakeholders and confronting challenges posed by diverse national and global factors from socio-legal human rights perspective needs to be adhered to. Ethnic handloom being also a cultural heritage for Bangladesh an indigenous stature of the aspect should also be taken as imperative.

A full-fledged handloom legislation and policy should be made covering all the relevant aspects in this sector i.e. re-affirmation of it as a cultural and national legacy, investment policy, protection of weavers from intermediary exploitation, smooth administration of handloom tradition, proper equipment of Handloom Board, provision for soft loan, prevention of smuggling, importation of yarn, labor condition, women rights in the sector, ethnic dimension etc.

S. M. Masum Billah teaches Law at the Northern University Bangladesh and works with the Law Desk.