Human Rights war crimes

Trials of war criminals under International Humanitarian Law in Bangladesh

Professor Rafiqul Islam

|

bangladeshpatriotfederation.com |

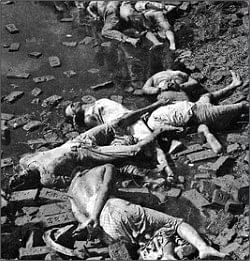

Demands for the trials of war crimes committed by Pakistani troops and their auxiliary forces and collaborators in 1971 are as old as Bangladesh itself. Prosecution, conviction, and punishment of the perpetrators of these crimes are on the increase both internationally and nationally. Internationally, these demands represent the quest of humankind to combat and prosecute certain designated crimes, namely genocide, crimes against humanity, and war crimes, as a collective bid to ensure dignified human coexistence. Nationally, the matter has been stirring the minds and emotions of many Bangalees since 1971. The gravity and extent of these crimes and the continuing impunity of their perpetrators have offended our cherished ideals of the liberation war the first ever successful exercise of secessionist self-determination in the post-colonial era. The prolonged inaction by the Bangladesh authority has solicited our attention, intruded onto our consciousness, and challenged our wisdom of inaction. Viewed from this perspective, the election pledge of the incumbent government to try the war crimes committed during the 1971 Bangladesh liberation war is, though belated, in order and indeed imperative. The government is specifically and overtly mandated to initiate this historic trial. This criminal trial entails many aspects. Of them the application of international humanitarian law is one. This brief legal note highlights and comments upon prospects and challenges in such application to try the war criminals of the Bangladesh liberation war 1971.

Seemingly prosecuting the crimes committed during the Bangladesh liberation war after 38 years is an ambitious task. Collecting credible and admissible evidence would be quite challenging. Nonetheless, there are certain advantages and precedents to be followed in pursuing this trial in Bangladesh. The international community and its forum, the UN, have been in favour of ending the impunity and immunity of the perpetrators of the designated international crimes by bringing them to justice. The UN has been instrumental in setting up international war crimes tribunals for former Yugoslavia and Rwanda. At the request of the Sierra Leone government, the UN set up the Special Court for Sierra Leone in 2002 to try the designated crimes committed during the civil war in Sierra Leon. The UN has also been actively involved in the ongoing special trials of genocide committed in Cambodia by the Khmer Rouge regime in the 1970s. This Cambodian trial may offer seductive lessons for the Bangladesh trial, as the designated crimes committed in about the same time and the evidentiary difficulties may well tend to be similar. If the Cambodian trial can proceed notwithstanding the time gap, there is no reason why the same cannot be accomplished in Bangladesh.

Bangladesh can initiate its trial under its International Crimes (Tribunal) Act 1973, which remains in force. The Act authorises the government to establish, by gazette notification, one or more tribunals to prosecute persons accused of genocide, crimes against humanity, and serious violation of the Geneva Conventions that took place in the territory of Bangladesh. Since these crimes are special in their legal nature and elements, usually special court or tribunal with specific mandates and jurisdiction is preferred. Such a special court/tribunal is capable of rendering expeditious and distributive justice by addressing usual procedural complexities involved in the ordinary criminal justice system. The readily available evidence of the commission of war crimes and their perpetrators are usually newspapers reports, special reports, photographs and footages, documentaries, tape recordings, hearsay, and the like, which are not necessarily admissible as a matter of fact in ordinary courts. It is this special factor that warrants special court/tribunal, which precisely led to the formation of special court/tribunal in Nuremberg, Bosnia, Rwanda, Sierra Leon, and Cambodia.

Section 19 of the International Crimes (Tribunal) Act 1973 permits the special tribunal to admit as evidence all reports, photographs, films and other materials having evidentiary or probative value. The prosecution can gather evidence from numerous sources scattered nationally and internationally. For example, the East Pakistan Staff Study of International Commission of Jurists (no. 8 of June 1972, pp. 23-62) vividly exposed the reign of terror, civilian killings, and wanton destruction by Pakistani troops and their auxiliary Razakars, Albadars, Al-Shams and other local para-militia in East Pakistan. NBC news report on 20 February 1972 showed the victims of genocidal rapes of Bangladeshi women and girls during the liberation war. In another NBC report televised on 1 July 1972 about the Dhaka University Massacre of 26 March 1971 and CBS news of 2 February 1972 showing evidence of mass graves and indiscriminate civilian killings. The report of Jake Hirsch-Allen entitled: Peace and Justice Implications of 1971 Bangladeshi atrocities of 25 July 2008 also affords evidence collected from Sunday Times, Time Magazine, and web sources.

The active involvement of the UN in the formation of the special court/tribunal and trial process would manifestly augment its credibility, neutrality, and international character and acceptance. The UN can even be partially involved in the prosecutor's office. For example, the Special Court of Sierra Leon is not only jointly administered with the UN, but also the Chief UN Prosecutor issued indictments and laid specific charges against individuals. Such a strategic approach may be warranted for making the trial apolical and wider acceptability and not to be viewed a dilution of national sovereignty. The UN involvement would also facilitate extradition and custody matters with less legal and procedural complexities.

This trial must happen not only to try the alleged criminals and to render justice to the victims and their relatives, but also to legally determine the crimes and identify their real perpetrators. In the absence of such legal articulation, the term “war criminals” in Bangladesh is used by and large with a political overtone and randomly, often against those political parties that opposed the 1971 liberation war. This generalised social hatred of “war criminals” is politically incorrect, legally offensive, and detrimental to nation-building, as there may well be some members of these political parties who neither opposed the liberation war, nor took part, directly or indirectly, in the commission of the alleged war crimes. Many have even born after 1971. A judicial determination of the true “war criminals” would go a long way in providing fairness and justice to these latter groups. So the trial is likely to serve the best interest of all stakeholders victims and so-called war criminals alike.

The trial of Pakistani nationals accused of committing these crimes may be comparatively complex and difficult than those of the Bangladeshi nationality. Section 3 of the International Crimes (Tribunal) Act 1973 provides that any tribunal established under this Act shall have power to try and punish any person accused of war crimes committed in the territory of Bangladesh regardless of their nationality. Theoretically, this provision mandates to try members of the Pakistani army who committed the war crimes and the politicians who ordered and presided over the commission of these crimes. Indeed, Bangladesh prepared a list of 195 Pakistani army personnel accused of war crimes and decided to prosecute them. Those listed war criminals were sent to Pakistan under the Shimla Pact on a pledge that Pakistan would prosecute them, which never happened. Nor did Pakistan act on its own Hamood-ur Rahman Commission's recommendation to “take effective action to punish those who were responsible for the commission of alleged excesses and atrocities” in East Pakistan. Bringing these listed criminals to justice now appears to be a daunting task.

However, there are pressing mitigating factors in favour of their trial. This immunity provided in the Shimla Pact exonerating the perpetrators of heinous crimes contradicts the international obligations of the Pact-states. The prohibition of genocide, crimes against humanity, and war crimes is a jus cogens principle (peremptory norm) of international law, which gives rise to erga omnes - an obligation “towards the international community as a whole” (ICJ in Bacelona Traction Case, 2nd phase 1970 at 32; also Namibia Opinion 1971and Nicaragua case 1986). The state parties of the Pact are obliged to perform this obligation by prosecuting the perpetrators of these crimes. This norm and obligation are highest in international law, which permits no derogation from them. This hierarchical status of their prohibition is based not only on customary international law but also reinforced through codification in Articles 53, 64, and 71 of the 1969 Vienna Convention of Law of Treaty. Article 53 prescribes international treaties conflicting with an existing jus cogens norm “is void”. Article 64 says that if a new jus cogens norm emerges, “any existing treaty which is in conflict with that norm becomes void and terminates”. Article 71 releases the parties to a treaty void under Articles 53 and 64 from any obligation to perform the treaty.

Genocide, crimes against humanity, and war crimes are well defined and punishable in customary international law, Hague Convention 1907, Nuremburg Judgement 1945, Genocide Convention 1948, Geneva Conventions 1949 and their protocols 1977. The culpability of these crimes and criminal responsibility of individual perpetrator are duly recognised in the mandates and judgements of Yugoslav and Rwandan War Crimes Tribunals 1993-94, the Statute of the International Criminal Court 1998 (Arts 6-8), mandate of the Special Court for Sierra Leone 2002, recently formulated mandate for the Cambodian Special Tribunal 2007 to prosecute the perpetrators of the 1970 genocide.

Indiscriminate killings of innocent and unarmed civilians committed by Pakistani troops and their local associates with the deliberately pursued intention of exterminating the Bengalis can come well within the purview of crimes of genocide. Widespread atrocities, tortures, inhuman, humiliating, degrading, and cruel treatment, disappearances, and systematic rape in 1971 clearly constitute crimes against humanity. The legal scope of rape inclusively include rape, sexual slavery, enforced prostitution, forced pregnancy, enforced sterilisation, or any other form of sexual violence of a comparable gravity committed on political, racial, cultural, religious, national, ethnic and gender grounds. Forced pregnancy constitutes genocide as it involves the unlawful confinement of women/girls forcibly made pregnant with the intent of affecting the ethnic composition of a population (Art. 7 of ICC Statute). The inseparable nexus between systematic rape and genocide is judicially endorsed by the ICJ in the case of Application of the Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide (Serbia and Montenegro) in 1993, the Yugoslav Tribunal in cases: Nikolic 1995, Milijkovic 1995, Meakic 1995, Karadzic and Mladic 1996, Tadic 1997, Furundzija 1998, and Kunarac, Kovac and Vukovic1999, and the Rwandan Tribunal in Akayesu case 1998. The Special Court of Sierra Leone prosecuted rape as a major war crime on its own right and independently of genocide and ethnic cleansing (indictments of 7 March 2003). The Pakistani army and its local allies throughout the liberation war caused massive destruction of houses, villages, towns, public utilities as reprisals, executions without trials, torturing sick and wounded, and taking hostages - some of the notable war crimes listed in the common Article 3 of the Geneva Conventions as well as their Additional Protocols.

Relying on the international instruments and judicial precedents referred to, it is possible to make a formidable case for arguing that grave breaches of international humanitarian law occurred during the Bangladesh liberation war in 1971 through the commission of genocide, crimes against humanity, and war crimes by the Pakistani army and their local associates. The prohibition of these crimes is recognised as a jus cogens norm of international law, which cannot be set aside by the Shimla Pact or the acquiescence of its parties. Indeed, the Shimla Pact is void to the extent of its inconsistency with, or repugnancy to, a body of existing jus cogens principles of international law. Its parties are totally released from performing the Pact obligations concerning the prohibition of war crimes trials. Criminal trials are always open and not barred by time limitation. This explains why the Nazi war criminals of the Second World War are still prosecuted. Trials of genocides committed during the 1973 Chilean revolution and the Pol Pot regime of Cambodia in the early1970s are now ongoing. The sovereign immunity of Slobodan Milosevic of Sebia, Charles Taylor of Liberia, and Augusta Pinochet of Chile (with the Chilean Senate life-long immunity) as the head of state could not protect them from being detained and prosecuted for committing genocides, crimes against humanity, and war crimes. The trial of a Congolese militia commander, Lubanga, for committing war crimes has started at the ICC on 26 January 2009.

The perpetrators of these crimes are hostis humanis generis (enemy of humankind) and jurisdiction over them is universal, entailing that any national or international court or tribunal can try them even in the absence of any linkage with the nationality of their perpetrators and/or the place of the commission of those crimes (Eichmann case 1962). The House of Lords has reinforced the exercise of universal jurisdiction over these crimes in ex Parte Pinochet No. 3 in1999. In view of these developments, there appears to be no insurmountable legal obstacles to prosecute Pakistani and Bangladeshi nationality for their alleged commission of genocide, crimes against humanity, and war crimes by constituting independent and impartial special tribunal.

International humanitarian law has become a defining norm of the international order, a meta-norm to combat some designated crimes in international law. These heinous crimes, though prohibited in all forms and manifestations, still stigmatise their victims more than their perpetrators. The Bangladeshi victims of these crimes and their relatives are no exception. The reversal of the stigma and mobilising the shame associated with these crimes from victims to victimizers is long overdue in Bangladesh. The statutes of various war crimes tribunals and International Criminal Court have already laid the historic foundation for prosecuting the alleged war criminals of the Bangladesh liberation war. The de-communalisation of the brand of communal politics that contributed to the commission of these heinous crimes in 1971 would go a long way in preventing similar crimes from committing in the future. The recent election mandate in Bangladesh has galvanised and realigned the popular demand for the trial further. The incumbent government must be responsive to this changed environment and the shared expectation of the people of Bangladesh.

The wrier is Professor of Law at Macquarie University, Sydney, Australia; teaches and has published extensively in the area of international criminal law and court.