Rights monitor

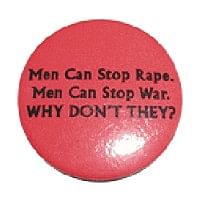

Rape in war: Will the UN walk its talk?

Oli Md. Abdullah Chowdhury

On June 19, 2008, the United Nations Security Council made history by declaring that rape in war is such a bad idea they plan to do something about it.

On June 19, 2008, the United Nations Security Council made history by declaring that rape in war is such a bad idea they plan to do something about it.

That's right. After decades of reports on vicious sexual violence in conflicts across the globe, the highest decision-making body of the United Nations has decided that it is time to act. In fact, no other international actor has as much power to do something about rape in war, and as disappointing a record, as the United Nations Security Council.

It is not that the Security Council hasn't talked about the issue before. In 2000, the Security Council -- under intense pressure from women's groups and UN field personnel -- established a link between the Council's mandate and the way in which women and girls are affected differently by conflict than men and boys. This link is contained in a resolution, known mostly by its number (1325/2000), which includes an urgent call to end impunity for sexual violence and for the United Nations system to gather information on issues related to women and girls in conflict and report these to the Security Council.

Action to back up these good intentions has, however, been scarce. Every year in October since 2000, the Council has celebrated the anniversary of resolution 1325 by announcing the importance of the gender perspective in its work, and then proceeded to largely ignore it for the rest of the year.

Up until last Thursday, that is. On Thursday, the Security Council declared its readiness to act on sexual violence in a resolution that contains three key components:

1. The resolution establishes sexual violence in conflict and post-conflict as a topic within the purview of the Council's work. "Obviously!" you might say, and you'd be right. There is no conflict in recent history where women and girls have not been targeted for sexual violence, whether as a form of torture, as a method to humiliate the enemy, or with a view to spreading terror and despair. If that's not potentially relevant to the protection of international peace and security, what is? But the inclusion of this clause is essential because some members of the Security Council, in particular Russia and China, at times have portrayed rape in war as an issue that doesn't deserve the Council's attention. With the new resolution, they will no longer be able to do so.

2. The resolution creates a clear mandate for the Security Council to intervene, including through sanctions, where the levels or form of sexual violence merit it. Again, this might seem self-evident. The Security Council is mandated under the UN Charter to address situations that present a threat to international peace and security. It has the power to chastise countries waging war without proper cause -- notably, not in self-defense -- or by illegal methods, such as the use of child soldiers and, indeed, using rape as a weapon of war. Despite this mandate, the Council has so far done little to prevent or punish states for rape in war. In fact, it would seem it at times has consciously avoided doing so. This was, for example, the case during the July 2007 discussions regarding the mandate-renewal for the UN mission in Côte d'Ivoire. Despite having received information regarding intolerably high levels of sexual and gender-based violence in that country, the Council did not empower its field staff to address the violence.

3. The resolution asks the Secretary-General to provide a comprehensive report on the extent to which the resolution has been implemented, as well as on his views on how to improve information flow to the Council on sexual violence. This is tremendously important. In the past, the prevalence and patterns of sexual violence have barely featured in the reports the Council commissions and receives from the field offices of the United Nations. This is in part because the Security Council until now more often than not didn't ask for such information to be included in the reports. This crucial failure has been addressed in last Thursday's resolution, which asks for information on sexual violence to be included in all reports. Still, the UN system may in many cases not be equipped to gather information on sexual violence in conflict-affected situations in a consistent and ethical manner. This is a root cause of the lack of Security Council attention to sexual violence. And last Thursday's resolution asks the UN Secretary-General to propose a lasting solution.

Thursday's debate and the resulting resolution also added a new word to the Council's sometimes dusty vocabulary: never before has a Security Council resolution called on parties to "debunk" myths that fuel sexual violence. But the historic contribution of Thursday's debate was to "debunk" the Council's own and self-perpetuating myth that sexual violence in conflict simply didn't happen because it didn't feature prominently in UN reports to the Council -- which, in turn, had been commissioned without seeking to elicit any information or insights on rape in war.

Of course, any UN resolution is only as good as its follow-up. In fact, it is possible that the Security Council's until now tepid attention to sexual violence in conflict-affected situations is a symptom of a more onerous problem: a deep-seated reluctance to address rape at all, mirroring the failure of national governments to prosecute and address violence against women more generally. Moreover, the UN system cannot change overnight: while it is now legally empowered to provide information on sexual violence in conflict situations, it still needs to be appropriately structured and resourced to do so. This requires investment in training and service-provision, and it requires the prioritization of this issue at the highest level: field missions, UN agencies, and peacekeeping troops should be evaluated, amongst other things, on the effectiveness and ethics of their approach to sexual violence. It is incumbent upon UN members states, Security Council members, UN agencies, and civil society to make sure this happens. The road was paved last Thursday. Now it's time to see if the United Nations can walk the walk.

Source: www.hrw.org.