Law Opinion

Prison reform is imperative

Dr M Enamul Hoque

The overall objective of this article is to identify ways of Jail Code for improving the prison system in Bangladesh, and to suggest ways to curb human security and human rights violations inside prisons. Specific areas of focus include overcrowding, delays in judicial proceedings, living conditions in prison, the operational environment and management of prisons, and infrastructure and facilities. Interviewees and respondents include members of the general public and the elite, prisoners under trial, convicted prisoners, prison officers, police officers, judges and lawyers.

The administration and management of the prisons in Bangladesh is carried out according to the rules and acts as enumerated in volumes 1 and 2 of the Jail Code, formulated by colonial rulers during the 19th century. These colonial rules and acts include the Prisons Act IX of 1894, as amended, relating to the management and training of prisoners; the Civil Procedure Code relating to the management of civil prisoners; and Act XLV of 1860, as amended, of the Penal Code.

The 64 prisons in Bangladesh can be divided into two major types:-

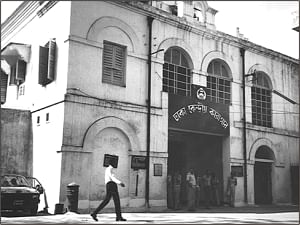

Central Jails are for the confinement of prisoners under trial, administrative detainees and convicted prisoners sentenced to a term of imprisonment, including imprisonment for life, and the death sentence. There are eight such central jails, which could also be called maximum-security prisons.

District Jails, located at the headquarters of the district, are used for the confinement of all categories of prisoners, except those convicted prisoners whose sentence exceeds 5 years. District jails also hold long-term convicted prisoners if ordered by the Inspector General of Prisons/Deputy Inspector General of Prisons. There are 56 such district jails, which could be called "medium security prisons."

District Jails, located at the headquarters of the district, are used for the confinement of all categories of prisoners, except those convicted prisoners whose sentence exceeds 5 years. District jails also hold long-term convicted prisoners if ordered by the Inspector General of Prisons/Deputy Inspector General of Prisons. There are 56 such district jails, which could be called "medium security prisons."

In addition to central and district jails, there are 16 thana jails, known as "detention houses," located at 16 thana headquarters. If thana jails are included, there are some 80 jails in Bangladesh.

The Ministry of Home Affairs, through the Directorate of Prisons, exercises overall responsibility for proper management of the prison system. Each prison is administered by sergeants, guards and other prison staff, under the supervision of the Superintendent of Jails. In the districts, the highest civilian official, the Deputy Commissioner, oversees the working of the jails, and is expected, along with district judicial officers, to visit the jails to supervise their management and receive complaints, if any, from the prisoners. Health services to them are provided by the staff of the district hospital. The main medical conditions for which prisoners are treated include diarrhoea and dysentery (42% of cases), fever, including typhoid fever (25%), skin diseases (20%), malnutrition (8%), psychological problems (1.5%), and heart problems (1%). The high frequency of diarrhoea and skin diseases is due to the poor sanitary conditions prevailing inside prisons.

In the recent past, overcrowding of prisons has worsened significantly. Although there are 80 jails in the country, 16 of these are not yet functioning. And whereas the official capacity in the remaining 64 jails is 21,581 prisoners, the actual prison population was about 46,444. Of these, 31,020 were under trial, i.e. detained prior to conviction, while only 13,178 (less than one third) were convicted prisoners. Hence, overcrowding of prisons is due mostly to the large number of prisoners awaiting-trail. This is considered to be one of the main causes of human security violations in Bangladesh.

Delayed processing of criminal cases is mainly due to (a) a backlog of cases in which bails are not granted; (b) non-attendance of witnesses on the date of the hearing; (c) unnecessary adjournment; (d) delays in completing investigations; (e) acute shortage of judges and magistrates; (f) tendency of lawyers and parties to delay trials; and (g) lack of vigilance on the part of judges and magistrates (as opined by learned judges, magistrates, and eminent lawyers).

Cell accommodation: This is for classified prisoners, execution of jail punishment, segregation of confessed prisoners, and prisoners condemned to death.

Association wards: There are for all types of prisoners, including hardened criminals, occasional offenders, and youth offenders. Prisoners are required to sleep together in single dormitories, accommodating 100 to 150 prisoners. Hardened criminals influence occasional and youth offenders who form gangs within the prisons, mostly with a view to committing serious crimes after they are released. Hence jails have become "storehouses" to train criminals, according to critics.

Moreover, floor space allocation bears witness to the poor conditions in which prisoners are kept. Under dormitory rules, each prisoner is entitled to 36 sq. ft. of floor space; however, overcrowding has reduced the space available per prisoner to 15 sq. ft. In certain wards, prisoners have to sleep in shifts owing to lack of space. Finally, life in prisons is made worse by the smell of carbon dioxide, nicotine, sweat and urine emerging from uncovered urinals, which create an unsanitary atmosphere inside the congested wards. These are painful examples of denial of the legal rights of inmates.

There are two kinds of diets for inmates. Ordinary prisoners receive 2,800 to 3,000 calories per day, which is considered satisfactory by the Institute of Public Health Nutrition. However, so-called "classified prisoners" receive an additional amount of food. The existence of this privileged class of prisoner creates dissatisfaction among ordinary inmates. Furthermore, the manner in which the prisoners are required to eat their meals sitting on the ground under the open sky, rain or shine, is unacceptable.

The current striped, coarse uniform worn by ordinary prisoners is considered most demoralising. A bed consists of two blankets one to spread on the floor, and another to use as a pillow -- this is both inadequate and degrading. Such conditions are detrimental to prisoners physical and mental health, and in violation of their human rights.

It is noted that prisons still follow the outdated statute books of the British colonial rulers, which were framed in the 19th century. According to these old statutes, the main objective of the prison system was the confinement and safe custody of prisoners through suppressive and punitive measures. There has been no significant modification in the jail code, nor have the vital recommendations of the Jail Reform Commission been implemented. A full transformation of this punitive system is required in order to stop violation of the legal rights and human security of prisoners, as guaranteed by Article 44 of the Constitution.

The recruitment and training procedures of prison officers and staff under existing rules and procedures are insufficient for the needs of prisoners. Prison services in most developed countries are considered to be quite advanced as correction officers are educating offenders, as part of the effort to facilitate the reform and eventual reintegration of prisoners into society. This contrasts with the prison system in Bangladesh, which is geared towards containment and punishment of prisoners, and does not facilitate their reform. Hence, prison officers and staff are not recruited with appropriate skills nor trained adequately to encourage reform. Thus the main problems are as follows:

* Inadequate medical facilities inside prisons.

* Lack of monitoring of prisons.

* Lack of welfare measures and reform programmes.

* Corruption in tendering contracts and interviews.

* Inadequate attention to women and child prisoners.

* Inadequate vocational training facilities.

Recommendations

Outdated laws and procedures concerning prisons should be amended to institute a more humane and sophisticated approach. It is important to promote the concepts of prison reform and the protection of human rights and security of prisoners based on the evidence that such treatment is more effective than retributive treatment. This is particularly true for vulnerable groups such as children and women.

So speedy implementation of the recommendation of the Bangladesh Jails Reform Commission Report of 1980 in order to reform the current punitive emphasis of treatment in Bangladesh prisons is imperative.

It is recommended that there should be separate prisons for female prisoners, near the larger central and district jails. The Prison Directorate should have its own medical services, with doctors who are interested in providing medical services in prisons as a career, to be recruited by the Ministry of Home Affairs through the Public Service Commission. Pathological, radiological and cardiological personnel and facilities should be made available in jail hospitals. There should be one part-time cardiologist with a technician for each central jail and complicated cases from the district jails could be transferred to the central jails for diagnostic tests and treatment; one well-equipped operation theatre for minor operations should be at every central jail.

Patients with complex cases should be sent to external hospital for specialised treatment. There should be separate segregated wards in prison hospitals to treat prisoners suffering from infectious diseases and drug addiction. The required number of modern appliances (X-ray, ECG, and reagents) should be procured from the central medical store or other sources. Facilities for the specialised treatment and major operations of ailing prisoners as existing in many developed countries, as well as in some developing countries, should be made easily available (such as postgraduate (PG) prison annex).

Better monitoring of the performance of prison staff should be undertaken in order to remove anomalies existing in prison administration. Formal complaint mechanisms for prisoners are recommended to reduce human security violations. The system of visits should be improved so that it provides checks and balances to the administration of prisons. There is a need to increase the capacity of the police to cope with improved techniques adopted by criminals and the alarming rise in crime rates.

Reforms, particularly prison reforms to deal with human security in our prisons, are understandably difficult to achieve. However, they can be brought about if concerted efforts are made by both govt. agencies in charge of prison administration and NGOs and civil society to improve prison systems. The govt. has taken up some projects to promote welfare of the inmates and bring them back to be integrated in society. Hopefully all concerned will take it as a moral commitment for upgrading the human dignity.

The writer, a former IGP, Bangladesh and former EC member, INTERPOL is a Member, Law Commission Bangladesh and President, Asia Crime Prevention Foundation.