Human Rights Analysis

Fallacy of generation-based human rights

South African experience

Shah Md. Mushfiqur Rahman

Human rights are often categorised into some broad divisions. These are -- civil and political rights on the one hand and socio-economic and cultural rights on the other. Our Constitution framers placed the civil and political rights in Part III of the Constitution under the title 'Fundamental Rights' and opted to put economic, social and cultural rights in Part II of the Constitution under the title 'Fundamental Principles of State Policy'. But what is the difference between 'Fundamental Rights' and 'Fundamental Principles'? A black-letter lawyer's answer would be prompt and outright, “fundamental rights are enforceable by law and conversely, fundamental principles are not.” Does that speak it all or there is more to it than mere enforceability as the only differentiating factor? First, let us consider the rationale behind this classification of rights.

This grouping of rights into separate categories is not quite unique to Bangladesh Constitution. Other constitutions of different jurisdictions also resorted to this method with subtle variations in the titles of categories. This classification of human rights was inspired by the theory of generation-based rights.

This grouping of rights into separate categories is not quite unique to Bangladesh Constitution. Other constitutions of different jurisdictions also resorted to this method with subtle variations in the titles of categories. This classification of human rights was inspired by the theory of generation-based rights.

This idea of generation-based human rights is credited to Czech jurist Karel Vasak. He formally placed this concept before the international community in 1979 at the International Institute of Human rights in Strasbourg. His basic idea was to divide human rights into three generations.

The first-generation human rights basically contain civil and political rights like -- freedom of association, right to movement, freedom of speech, right to vote, freedom of religion, right to fair trial etc. These rights are also called 'negative rights' in the sense that government need not do anything for realisation of these rights. All government needs to do is to abstain from interfering with exercise of these rights by the citizens.

On the other hand, second-generation human rights are mostly social, economic and cultural in nature. These include rights like -- right to food, clothing, health care, shelter, employment, social security etc. These are also known as 'positive rights' in that government has to do something affirmative to get these to people or help people achieve these.

The third-generation human rights are more progressive than the former categories so as to include rights like -- right to healthy environment, right to development, right to self-determination etc.

It was once believed that socio-economic rights would be within reach in the course of time if civil and political rights could be materialised to a reasonable degree. In other words, civil and political rights are of enabling character, exercise of which will facilitate the achievement of secondary kind of rights i.e. rights of socio-economic character. But practical scenarios of economically weaker countries disprove this widely professed 'chain reaction' of rights. Exercise of first-generation rights for several generations failed to bring the second-generation rights within peoples' accessibility in these countries. With the development of this understanding, the concept of grouping human rights into different generations started loosing its weight, substantially.

Now progressive jurists agree that human rights are to be seen in totality. One set of rights could prove of little use if other set remains unaddressed or underemphasised. Say for example, if a child is not provided with one vital social right i.e. right to education, he is unlikely to get a well-paid job on reaching his adulthood and here right to equal treatment of law (alleged to be a first generation right) would be of no avail for him.

In absence of socio-economic rights, full realisation of civil and political rights is not possible and the vice-versa. So both sets of rights complement each other as they are mutually enabling in nature. And the strongest argument advanced for not providing enforceability of 'positive' rights is also somewhat misleading and more often than not overemphasised. Practically, enforcement of 'negative' rights is not all about mere abstention on the part of the government. Say for example, maintenance of law and order situation, which is central to create congenial atmosphere for enjoyment of 'negative' rights, requires government to incur as much or more resource than that required for enforcement of any 'positive' right.

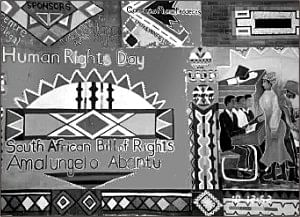

South Africa had the luxury to take lessons from the constitutional experience of some other countries which find it difficult to strike a balance between 'positive' and 'negative' rights, in terms of their respective importance including enforceability. Exploiting this lessons to their full advantage and showing adherence to the indivisible nature of human rights, South Africa, that framed its constitution in 1996, resolved to put all the rights in the same part of the Constitution they named 'Bill of Rights'. But welfare rights like access to housing, health etc. are not made enforceable in the same way as other classical rights.

The provisions say that the state is under a duty to make these rights realisable through reasonable legislative and other measures, which must serve progressively to enhance access to these rights, bearing in mind the financial capacities of the state. Some would find it difficult to identify what advancement it did make over Bangladeshi position on socio-economic rights. The difference is subtle but fundamental and decisive. As would be seen in the instance given below, the position of South African constitution on socio-economic right brings the issue of availability of resources in fulfilling the rights within the boundary of judicial review. Stated simply, South African Constitutional Court is authorised to scrutinise whether the state has enough financial capacity and whether this capacity is used to its fullest. In Bangladesh we have left the issue totally at the mercy of political will of government.

Now let us see some of the fruits South African innovation has yielded so far. The judgment delivered in the famous Grootboom's case (2000) by the South African Constitutional Court sheds some light on the advancement that South African Bill of Rights may have made vis-à-vis our Fundamental Principles. In this case several hundred homeless people, occupying government land without any legal authority, were evicted leaving them roofless. They had section 26 and 28(1)(c) of the Constitution in their favour which gave them the right of access to adequate housing and afforded children the right to shelter respectively. But the problem was that neither of the sections entitled them to claim the implementation of the right to shelter immediately. Rather it was made dependent on the availability of governmental resources.

This delicate case put the perceived progressiveness of the South African Bill of Rights to serious test as the way letters of law to be applied in negotiating practical situations was to set the direction of South African Constitution so far it concerned implementation of socio-economic rights. In a unanimous judgment the Constitutional Court stressed that all the rights in the Bill of Rights were inter-related and mutually supporting as realisation of socio-economic rights were to enable people to enjoy the other rights enshrined in the Bill of Rights. Thus, human dignity, freedom and equality were denied to those without food, clothing or shelter. Then the Court ventured to evaluate some housing programmes already taken by the government, assessed their efficiency and gave some specific directions meant to ameliorate the conditions of the aggrieved petitioners.

It appears that the inclusion of socio-economic rights alongside 'classic' liberty rights already produced some benefits as this allowed the Constitutional Court to accord more importance on such socio-economic rights and intrude into the domain of governmental policy making and programme implementation in ensuring these rights. Though the Constitutional Court did not deny the Constitutional qualification of 'availability of resources' in implementation of socio-economic rights, it did assume the authority, which of course is a responsibility too, to investigate into the availability of resources and make directions, as they find appropriate on their findings of investigation, to the government. In other words, in appropriate circumstances, the Court can and must enforce governmental obligations of socio-economic nature.

South Africa has shown its maturity by taking lessons from the development of different nations' constitutional jurisprudence. Its Bill of Rights and Constitutional Court's response to that really marks a giant leap towards converting the country into a welfare state. Now it's our turn to take lessons that are being yielded by South African Constitutional development. We must remember that if the socio-economic rights remain underachieved, enforcement of civil-politico rights would just help the beneficiaries of a class-stratified and discrimination-ridden society to maintain a status-quo. So it is for the greater goal of bringing structural change and thus help the toiling masses to live more human-like lives, we should closely see and adapt South African experience to best suit our own situation.

The author is an advocate and member of Dhaka Bar Association