Star Law vision

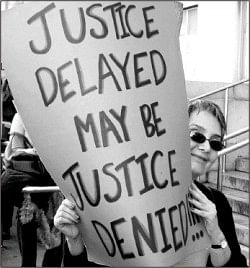

Justice delayed, justice denied

Syed Mujtaba Quader

The quickness in the dispensation of justice, and the degree of empathy society has for the disadvantaged, are two of the most important measures of the state of advancement of a nation. On both counts we Bangladeshis fall far behind. No money or investment is required to attain this -- all that is required is the cultivation of a state of mind. With the growth of multifaceted NGOs and the presence of a vociferous civil rights community the disadvantaged may find some solace in recent times.

The quickness in the dispensation of justice, and the degree of empathy society has for the disadvantaged, are two of the most important measures of the state of advancement of a nation. On both counts we Bangladeshis fall far behind. No money or investment is required to attain this -- all that is required is the cultivation of a state of mind. With the growth of multifaceted NGOs and the presence of a vociferous civil rights community the disadvantaged may find some solace in recent times.

But, the dispensation of quick justice seems to have taken a back seat in a pseudo-democratic environment where political parties take advantage of the ignorance of the common people and the greed of the privileged ones. The more that one can use the judicial system for one's own selfish ends, the more successful he is. The legal system seems to have become a tool for the clever, the wily and the unscrupulous to the detriment of the entire nation. Individuals vie with each other to climb the mountains of achievement through the dishonest manipulation of the judicial system but they cannot see that the whole mountain is sinking in an abyss of wrong and evil.

After all, justice is the defining periphery for the value system of a people. By definition, if there is no value system there can be no justice, and conversely, if there is no justice there can be no value system. Moreover, if justice cannot be delivered over an extended period of time, then it can be said that there is no justice during that period of time. 'Justice delayed is justice denied' the famous quotation from British Prime Minister William Gladstone is well understood by schemers who have learnt that delaying justice is the way to defeating justice. Their mode of operation is quite clear -- delay justice and you have control over the authority that be. And by extension, you have power over the whole system and the nation.

In recent times, delaying justice has become the most important tool for unscrupulous people to be outside the system and eventually to manipulate the system from this vantage point. Going to court is the easiest way to win time and thereby have control over the situation. 'Not to decide is to decide' and if indecision can be forced upon the rightful adversary through the workings of the court, the decision will always favour the wrongdoer. The principal cause for the deflowering of our value system is the inability of our intellectuals and the legal system to recognise this.

How many land grabbers do we know today who have gobbled up land of hapless villagers just by registering a case in the local court? How many dishonest businessmen do we know who have stopped banks from foreclosing on mortgaged property by starting a court case? How many builders do we know who build huge buildings openly disregarding established building codes only by virtue of a court case. How many tenants do we know who go on occupying other people's property by just registering a court case? How many families around the country remain perpetually enmeshed in torment and anguish on account of a few square yards of inherited property because of one single court case? The list goes on and on.

Delay in deliverance of justice is eating away the fabric of the whole society. According to a study, 186 million people of the country are embroiled in some court case. This is more than the population of the country because some people are involved in multiple court cases. According to the same study the average time taken for a court case to be resolved in Bangladesh is 9.5 years. Some court cases have been known to go on for 50 years. In many cases the initial need for instituting a court case gets extinguished by the time a verdict is given by the court. And it goes without saying that the winner in these cases is the wrong-doer.

The lower judiciary is the most affected. Court cases linger for years and years and litigants cannot go to a higher authority when the lower court itself seems delinquent in its responsibility to delve out justice. It is important to note here that, although legal cases are almost always taken to the High Court by the losers for getting better judicial dispensation, getting out of the lower court itself may become an almost Herculean task, win or loose. There are quite a few ways that these delays take place. The first is by a combination of skilful lawyers and insensitive judges finding many causes for deferring hearing of the cases month after month for no rational reason at all excepting insensitivity and lethargy in carrying out their work. Sometimes dates are given two months away for no relevant reason at all. No methods exist for the litigant to appeal to a higher authority to seek redress from these whimsical actions of delay which over an extended period of time tantamount to the denial of justice.

The second is by lawyers who take the cases from court to court on flimsy technical grounds in a labyrinthine exercise of slippery judicial process that never finds traction anywhere. The third is allegedly by collusion between opposing lawyers who find much financial benefit in letting the case drag on and on for years. The fourth is by judges delaying the process as much as possible for reasons best known to them but that breed suspicion in litigants' and others' mind. The fifth is by court officials in charge of court documents and procedures who subscribe to all forms of stratagems to prolong cases for financial benefit. This list may go on and on. In all these cases who benefits the most is the person who is in the wrong, be it the litigant, the lawyer, the court official or the judge.

Although edicts have been promulgated in the past by various governments to speed up the workings of the lower court, in practice, these have been mostly unsuccessful because of other technical legalities that supercede these edicts. Avenues for appeal to a higher authority against the inactions of the lower courts have been conspicuously neglected in these edicts.

In this confusion and chaos the only leverage that a litigant can reasonably apply is to be able to choose and change lawyers at will depending on how much benefit a litigant perceives to be receiving from the person who is supposed to represent him and his interests in the court. It is a fundamental fact that a litigant goes to court with the intention of asserting his lawful rights, in other words, to win the case. If there was no possibility of winning a case the litigant could not be expected to go to court at all -- the litigant would have to yield and submit to the stronger adversary outside of court. The only exception as explained above is the self-confessed and unashamed wrong-doer who goes to court with the only intention of delaying resolution of the issue and thereby benefiting from the delay.

So, in order to win the case, the litigant is pre-disposed to selecting the best person in his understanding to represent him to win the case. This right of the litigant to choose and select a lawyer of his liking is fundamental to the disposal of justice in the present system. Market forces are supposed to play their role in fostering excellence in the legal profession. Instead, even this fundamental right of the litigant is being infringed upon in our present day judicial practice. The Bar Council has made it a rule that a lawyer once empowered to handle a case cannot be changed without a formal written release from the lawyer. Courts do not accept changes in legal representation without clearance from earlier representatives.

Obtaining exception to this requirement is lengthy and cumbersome. This involves making an application to the Bar Council and obtaining a ruling in this regard. This is almost impossible to do for common litigants with no knowledge of the law. The argument may be that this aspect of the practice prevents litigants from not paying fees to lawyers. Although, this may be true on paper, lawyers are known to use this ploy to keep clients tied up to themselves for years on end for benefit only to themselves with no caring at all to the actual cause of delivering justice.

No issue can be more paramount in the judicial system than to deliver justice to litigants. Petty attempts of lawyers and their associations to protect their own interests ahead of the interests of the litigant are repugnant in the least. This kind of anti-competitive practice breeds incompetence in the legal profession and thereby ultimately harms the litigants' and the public's interests. If it came to that, lawyers could always take delinquent litigants to task through the courts themselves. In actuality the complexity of this issue is reportedly compounded by the lawyers themselves allegedly by not presenting exact rates and prices for their services beforehand to inexperienced litigants. Market forces are disregarded by not allowing lawyers to advertise in any form thereby keeping litigants at the mercy of lawyers who are wary of competition from younger practitioners.

Attempts are lately being made by the present caretaker government to separate the judiciary from the executive branch. How successful this will be will depend to a large extent on the good will and cooperation of the Bar Council and the Bar Associations in initiating reforms in their rules and ranks to reflect the requirements of modern times and the needs of the litigants in the interest of law, justice and good governance.

Finally, we need to remember the famous quotation from the English philosopher Edmund Burke who said, 'All that is necessary for the triumph of evil is for good men to do nothing'. If we do not do anything to protect the right-doer and punish the wrong-doer then we cannot blame anyone if the knife is pointed in our own direction tomorrow.

The writer is a freelancer.