Law opinion

Judicial

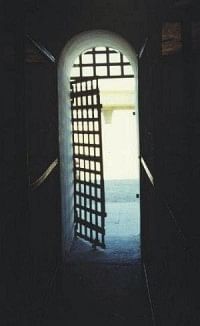

lock-up in Shikarpur

Anees

Jillani

It

is against the law in Pakistan, and perhaps for that matter,

in almost all the civilised countries of the world, to

keep children with adult prisoners. I need not explain

as to why this norm is practised. The colonial rulers

introduced the formal system of prisons in the Indian

Subcontinent, and soon thereafter also advanced the notion

of keeping juvenile prisoners separate from the adults.

Concepts such as Borstal Schools and Reformatory Prisons

were initiated for the first time in this part of the

world.

It

was nothing but shocking then that children in certain

prisons in the interior of Sindh were being kept with

the adult prisoners till very recently. The military a

couple of years ago tried to remove the children from

the adult barracks in the Sukkur and Hyderabad jails and

it led to serious riots. Fortunately however, the authorities

eventually succeeded in segregating the children from

adults.

I

had thus had no option but to visit the Judicial Lock-up

in Shikarpur (also known as Mukhtiarkari) during my recent

visit there when I was told that children were being kept

there with the adults. What I saw there is indescribable,

and could lead to innumerable suspensions, eventual dismissals

and resignations, and even toppling of governments in

another country. Not here of course.

The

clean shaven Mukhtiarkar at the Lock-up, Mr Imtiaz Ahmed

Mangi, appeared an educated, decent and friendly person.

But he looked so out of place in a building which was

perhaps more than 150 years old, and one-third of which

had almost collapsed. What looked hilarious was hundreds

of sacks lying in a room with a collapsed roof totally

covered with dust and some spilling paper all over. I

told him that I wanted to visit the Lock-up and he looked

bewildered. He was perhaps expecting me to express an

interest in some major real estate deal. So without wasting

anytime, we moved to the so-called jail. I told him that

I am primarily interested in meeting any under-18 prisoner:

there was one.

The

clean shaven Mukhtiarkar at the Lock-up, Mr Imtiaz Ahmed

Mangi, appeared an educated, decent and friendly person.

But he looked so out of place in a building which was

perhaps more than 150 years old, and one-third of which

had almost collapsed. What looked hilarious was hundreds

of sacks lying in a room with a collapsed roof totally

covered with dust and some spilling paper all over. I

told him that I wanted to visit the Lock-up and he looked

bewildered. He was perhaps expecting me to express an

interest in some major real estate deal. So without wasting

anytime, we moved to the so-called jail. I told him that

I am primarily interested in meeting any under-18 prisoner:

there was one.

The

child had an infected gun shot wound, and was lodged with

about sixty other prisoners in one room. I had never seen

such a thing in my life despite the fact that I must have

visited several dozen prisons in my life. The people behind

the bars across myself hardly had room to stand what to

talk of sleeping in that place. While talking to the prisoners

I noticed that there was a hole leading to an adjoining

room. I was relieved but not for long for when I walked

a few steps, I noticed that it was equally full. Where

is the toilet I enquired the prisoners. Right behind them

in a corner. I told the Mukhtiarkar that I had to see

it. He said that he would not advise me as he could not

guarantee my security once I enter the barrack. I told

him that I was willing to take the risk; and all this

conversation was going on in front of the prisoners. So

the guard reluctantly and cautiously but of course dramatically

opened the barrack iron gate. I entered and the prisoners

suddenly lined up on both sides and started shaking my

hands and a plethora of complaints started. I reached

the toilet; it was clean and I was happy. It goes without

saying that the prisoners themselves had to clean it as

the prisoners in Pakistan are invariably their own bonded

labour.

I

asked Mr Mangi as to what kind of hell is this? And can

it get worst than this? I told him that at least release

the child, particularly so because he had committed no

crime and was only picked up by the police following his

gun shot wound after an inter-village feud. He said that

it was not possible. I am always reluctant to act as sureties

or guarantors for anybody but ended up even offering myself

as the child's guarantor: Mr Mangi said that he was helpless

as he did not have the authority to release the child.

We

kept walking towards the other remaining barracks (there

were a total of six) and I could not help noticing that

the number of inmates kept thinning out until we reached

the last barrack where there were only a few prisoners

in the whole room. Now do I need to explain the reasons

behind this luxury? And the last two barracks were the

only ones that were getting any sun light. The others

did not get any. One prisoner was even openly using a

mobile phone and I could not help recalling the recent

action taken by the Supreme Court of India against the

Bihar Government for letting a sitting MLA from the ruling

party use his mobile phone from the prison.

On

the one hand was the under-18 prisoner and then I came

across an around 75 year old man. He was shaking extremely

violently and my first reaction was that he was perhaps

simply acting in front of me. I told him to stand still

but the other prisoners told me that he was not acting

and this is how is shaking all the time. His crime: shooting.

The guy could not shoot an elephant, unless he was really

a good actor.

There

are a couple of things now that should be kept in mind

about the Shikarpur Mukhtiarkari. It was a Judicial Lock-up

and there were thus no convicted prisoners. Almost 90%

percent of captives eventually are absolved of all charges

and unconditionally released by courts. What would be

the compensation to the 270 under-trial prisoners locked

in this Lock-up? Had it been the United States, they probably

would have ended up recovering millions as damages. Here

all they could earn from the courts of laws are lots of

tareekhs (adjournments).

The

second point about this Lock-up was its over-crowdedness.

It was simply unbelievable to see so many people lodged

in one room. And the crux of this whole phenomenon is

the fact that there is a newly built District Prison in

existence in Shikarpur that is lying unutilised for the

past three years due to bickering amongst the various

departments in the Government of Sindh. I leave it to

the Government officials to explain the reasons for the

delay in making the prison operational. But regardless

of the basis, and how good it may be, how would anybody

in the Government of Sindh explain the misery of these

prisoners living in the enlightened moderate Republic.

Mr

Mangi nice as he was insisted on my taking cold drinks

and biscuits in his office. It was hard to do this after

seeing all of the agony. I called the DCO - District Co-ordination

Officer from his office enquiring as to why is the Government

not transferring the prisoners to the newly built prison.

He said that he was helpless and instead asked me to help

him. Strange? This Lock-up is not a normal one and so

the prisoners are not even allowed to go out at any time

of the day. You can imagine the plight of the ones who

are living in the barracks that are not getting any sun

light in this cold. All kinds of ailments in such an environment

are simply expected to be part of life. Mr Mangi mentioned

in passing that scabies is one of the most common ailments

in this place: the biscuit almost fell out of my hands.

I found an excuse to rush to his toilet to wash my hands

but there was no water. I found some drinking water to

clean my hands. Hands hopefully were free of scabies but

the mind has developed bad patches about this strange

system obtaining in our Land of the Pure.

The

author is an Advocate of the Supreme Court of Pakistan.