Israel's

killing of hamas leaders

Mayur

Patel

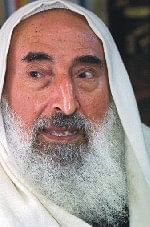

The April 18th killing in Gaza of Hamas leader Abdel Aziz Rantisi, following

on the heels of the killing of his predecessor, Sheik Yassin, provoked

an international outcry about Israel's policy of targeted killing. Such

tactics have been widely condemned as unlawful under international law.

In contrast, the United States, while occasionally uncomfortable with

Israel's policy, has acknowledged that Israel has a right to self- defence

that could be used in some circumstances to target leaders of terrorist

groups much as the United States has asserted its own right to target

Osama Bin Laden. From a legal standpoint, there are three critical issues

that determine the validity of this policy: the law of self-defense;

international humanitarian law; and the principle of proportionality.

A good faith analysis can lead to differing conclusions on the legality

of Israel's policy.

Self-defense

A key determinant in assessing Israeli policy is whether it is for the

purpose of self-defense or whether it is a reprisal. The concept of

self-defense in international law has two primary sources. First, there

is an explicit reference to self-defense in Article 51 of the U.N. Charter,

which states: Nothing in the Charter shall impair the inherent right

of individual or collective self-defense if an armed attack occurs against

a Member of the United Nations, until the Security Council has taken

measures necessary to maintain international peace and security.

Measures

taken by Members in the exercise of this right of self-defense shall

be immediately reported to the Security Council and shall not in any

way affect the authority and responsibility of the Security Council

under the present Charter to take at any time such action as it deems

necessary in order to maintain or restore international peace and security.

Measures

taken by Members in the exercise of this right of self-defense shall

be immediately reported to the Security Council and shall not in any

way affect the authority and responsibility of the Security Council

under the present Charter to take at any time such action as it deems

necessary in order to maintain or restore international peace and security.

Those who argue

in favor of Israel's right to self-defense in this situation hold that

Hamas's numerous suicide bombings against Israel constitute an armed

attack, much as the United States has argued that the use of civilian

airliners to destroy the World Trade Center constituted an armed attack.

Furthermore, they note that Hamas has openly declared its intention

to strike Israel again. Israel faces an ongoing threat and the Security

Council has not yet acted. Consequently, they argue that Article 51

provides Israel with a right to employ military force against Hamas's

leaders.

Those who dispute

Article 51's applicability generally do not dispute that the number

of Israeli casualties is substantial. However, the issue for them is

that an armed attack within the meaning of Article 51 is an armed attack

from a state. Hamas

is not a state. It cannot even be argued to constitute a de-facto state.

According to this view, Hamas's attacks are more akin to the acts of

a violent gang, which must be dealt with as a law enforcement problem.

Consequently, Article 51 would be inapplicable and the targeted killings

would be unlawful reprisals or extrajudicial acts of homicide.

The other legal

source of self-defence is customary international law. In particular,

many scholars cite the Caroline doctrine, which sets forth the standard

for anticipatory self-defense in customary international law.

The Caroline doctrine

arises from an incident in the 1840s where British soldiers crossed

into the United States to destroy a ship ferrying arms to insurgents

in Canada. Both the United Kingdom and the United States agreed that

anticipatory action was allowed only when the necessity of that self-defence

is instant, overwhelming, and leaving no choice of means, and no moment

for deliberation. After World War II, the Nuremberg Tribunal reaffirmed

the Caroline doctrine.

It should be noted

that after the advent of the U.N Charter, the Caroline doctrine is not

universally accepted; many reputable scholars have argued that Article

51 of the UN Charter supercedes it. Even conceding its validity, though,

reasonable individuals can come to differing conclusions on its applicability

in various situations.

For example, most

would agree that missiles being fueled for launch are an imminent threat

under the Caroline Doctrine. Few would concede, however, that mere discussions

on the construction of such weapons constitute a threat under this standard.

However, reasonable people could come to differing conclusions about

whether the actual shipment and emplacement of such weapons, for example

during the Cuban Missile Crisis, gives rise to a right of self-defense.

In that instance, the United States chose not to justify its interdiction

of Soviet missiles bound for Cuba as a measure of anticipatory self-defense.

In the present situation,

some of the recently targeted individuals such as Rantissi and Sheik

Yassin were not killed while in the process of carrying out an attack.

However, they were presumed to be in a position to order future attacks.

The more one agrees with Israel's assessment that the targeted individuals

were "ticking bombs," the more one would believe that a right

under the Caroline doctrine arises. One could also argue that since

Hamas has already carried out attacks, the Caroline doctrine is inapplicable

in a strict sense, even though it remains relevant to show that customary

international law recognises a right of self-defense.

International

humanitarian law

Another legal issue about Israel's policy is whether it comports with

international humanitarian law, which comprises the rules that govern

the conduct of armed conflict. Under this one question that needs to

be resolved is whether those targeted are combatants. The Geneva Conventions

on the Law of War, particularly common Article 3, prohibit the intentional

killing of civilians. Common Article 3 prohibits:

"(a) violence

to life and person, in particular murder of all kinds, mutilation, cruel

treatment and torture;"

and "(d) the passing of sentences and the carrying out of executions

without previous judgment pronounced by a regularly constituted court,

affording all the judicial guarantees which are recognized as indispensable

by civilized peoples."

Other international

human rights instruments, such as the International Covenant on Civil

and Political Rights, state that arbitrary execution is unlawful. Individuals

who belong to the military wing of Hamas, such as Rantissi, are likely

to be considered combatants. Individuals like Sheik Yassin, who was

a quadriplegic and supposedly a spiritual rather than military leader,

may be subject to more debate on their status as a combatants. Targeted

killings also implicate the Regulations annexed to the Hague Convention

of 1907, which are widely viewed as customary international law. It

is believed that most targeted individuals have been killed in helicopter

strikes. The Hague Regulations prohibit the killing or wounding treacherously

of individuals belonging to a hostile nation or army. Killing or targeting

particular individuals during an armed conflict is not illegal in itself

under international law, nor is it accurately described as assassination,

if the individuals are members of a hostile force. For example, the

United States' targeted attack on Admiral Yamamoto during the Second

World War was widely considered to be legitimate. The key issue in deciding

legality in such cases is whether or not perfidy or treacherous means

were employed.

The employment of

treachery is what distinguishes assassination from a traditional killing.

Killing individuals by a helicopter strike is generally an accepted

tactic of warfare .More stealthy means, however, could be considered

as acts of treachery. Some would also argue that persons at mosques

or in prayer have no means of defence and thus are impermissible targets.

The question becomes murkier, though, if such individuals are inciting

followers or giving orders at those facilities for hostile acts against

an enemy.

Proportionality

The last key issue regarding Israel's policy is whether it violates

the basic international law principle of proportionality. Proportionality

holds that any given action by a state must be substantially proportional

to the given threat or wrong. Israel's policy of targeted killing has

resulted in the deaths of multiple civilians. Were those deaths avoidable

if different tactics were utilised? Proportionality analysis depends

upon the circumstances and the situation. Many have suggested that Israel

had a less violent option at its disposal: an arrest. As the occupying

power, Israel could potentially deploy troops or police to arrest these

individuals.

Proportionality

is an important rule that could distinguish Israel's policy from the

American attack on terrorists in Yemen last year via a predator drone.

An arrest may be infeasible in the middle of a lawless dessert in Yemen.

Civilians are also unlikely to be wounded in such an attack; thus the

attack is likely to be proportional under the circumstances.

Whether Israel's

policy is proportional is not an open and shut case. Deploying soldiers

or police to apprehend suspects in hostile urban areas is a dangerous

affair. Whether more lives are put at danger through an attempted arrest

or a helicopter strike is debatable; hence the proportionality of Israel's

policy is unclear.

Concluding

Remarks

Israel's policy of targeted killings raises serious questions of international

law, but the answers are not obvious. Although observers view the policy

as contravening international law, there is a substantial amount of

uncertainty regarding the application of the relevant law to the situation

at hand. Thus, good faith analysis could lead to starkly different conclusions

on the legality of any such policy.

Source

: American Society for International Law (ASIL), New York.