(Un)weaving a Tale: Reading Penelopiad

Radha Chakravarty

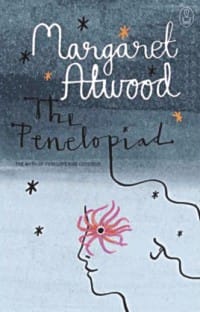

A man smitten by wanderlust, who is also a compulsive adventurer, a consummate liar, and a wily strategist with extraordinary survival skills. A woman who turns her long wait for her absent husband into a lesson in endurance, human resource management and ingenuous dissimulation. A host of suitors vying for the (unavailable) heroine's hand. The devastatingly seductive "other" woman, for whom thousands of men are ready to lay down their lives. Twelve serving women caught in a web of palace intrigue. Clashing egos, flashing swords, mangled bodies and tangled relationships. Rumour, scandal, blood, sex, violence and betrayal. The perfect formula, we could say, for an all-time bestseller. Homer certainly knew the secret of telling a good story, for since its inception many centuries ago, The Odyssey has always been in the news.What happens when the same story is retold by a woman, especially when that woman happens to be Canadian writer Margaret Atwood, also a storyteller with a miraculous success graph and a penchant for staying in the news? What happens to the story when its central figure is no longer Odysseus but his long-suffering wife Penelope, that legendary icon of female constancy? Or when this twenty-first century remake comes interlaced with a chorus line comprising the plaintive voices of the twelve maids hanged for conspiracy after Odysseus' return? For Atwood's Penelopiad (Penguin Books India; 2005) sets out to explore two questions that persist after we have read the Odyssey: "what led to the hanging of the maids, and what was Penelope really up to?" (xiv). The possible answers lie very often in sources beyond the Homeric text, Atwood affirms, highlighting the oral, locally variable versions of the myth that she also draws upon. Myth, by some accounts, offers us ways of encoding and interpreting our experience of the world. The world that Atwood's narrative presents to us is simultaneously archaic and modern, remote yet heartbreakingly close to home. Atwood has acquired a global reputation as novelist, short story writer and poet, not to mention her feminist and humanitarian leanings. All these facets of her genius are in evidence in this slim and deceptively light-sounding work, which brilliantly offsets the realm of myth against the cultural icons of today. Irony is the primary mode of this gendered retelling of the time-honoured legend of Odysseus and Penelope. Seen through Penelope's eyes, the politics of the old-time world strike us as primitive yet recognizable. The world she inhabits is starkly patriarchal, double standards nowhere more visible than in the contrast between Odysseus's compulsive womanizing during his travels, and the constancy he enjoins upon his wife. Odysseus' possessiveness about Penelope is impressed upon her mind through the threatening presence of the bedpost carved from a growing tree in their bedroom, a secret never to be shared by her with any other man. "If the word got around about this post, said Odysseus in a mock-sinister manner, he would know I'd been sleeping with some other man, and then . . . he would be very cross indeed, and he would have to chop me into little pieces with his sword or hang me from the roof beam" (59). Penelope pretends to be afraid, but as she confesses to the reader, "Actually, I really was frightened." Many years later, when Odysseus ruthlessly slaughters her suitors and dispenses with her twelve maids, we realize that Penelope's fears were not unfounded. In this men's world, women are sometimes allies, and sometimes their own worst enemies. As the young Penelope watches from the sidelines while prospective grooms compete for her hand, Helen of Troy, her cousin and arch-rival, crushes her with a deliberately cutting remark: "She and Odysseus are two of a kind. They both have such short legs" (27). Painfully aware of her own plainness, Penelope laments: "Why is it that really beautiful people think everyone else in the world exists merely for their amusement?" (27). Even after both women have joined the dead in Hades, nothing really changes: Penelope watches with envy as Helen's spirit sweeps by, trailed by a host of admiring (male) spirits. In Atwood's mythical universe everyone, god or hero, has feet of clay. During her struggle to survive her years of loneliness, Penelope emerges as a woman of ingenuity and great presence of mind, as she manages palace affairs, handles her difficult son Telemachus, and holds her suitors at bay. Her most triumphant achievement of course is the shroud she supposedly weaves for her father-in-law, unraveling it at night to postpone her decision to remarry. But her closest allies, the twelve maids, hint at a less innocent version of Penelope's story. The maids provide an earthy counterpoint to the high-flown rhetoric of heroic myth, hinting at less-than-glorious secrets and constantly keeping in view the way they are exploited by those in power. There is much in The Penelopiad that is vivid and memorable. But the image that persists long after we have closed this delightful yet deeply disturbing book is of the row of hanged women, their legs twitching in a grotesque travesty of the modern-day chorus line, to the end protesting their fate: we are the maids

the ones you killed

the ones you failed

we danced in air

our bare feet twitched

it was not fair The maids, Atwood tells us, represent a "tribute" to the choruses of Greek drama, whose role it was to burlesque the main action; but the line dividing then from now, The Penelopiad suggests, is really very thin. Radha Chakravarty is an academic and translator.

|

|