Book Review

"Is anyone in America reading The Reluctant Fundamentalist?"

Charles Larson

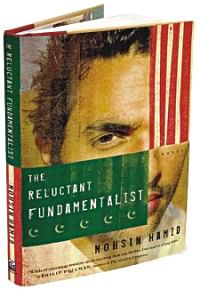

The Reluctant Fundamentalist by Mohsin Hamid; Harcourt, Inc.; 2007; 184 pages; $22.00In an interview he gave with 'The Stanford Daily' last month, Mohsin Hamid--author of the riveting new novel The Reluctant Fundamentalist--stated boldly, "I am in love with America and deeply angry with it, sort of like Changez" (the main character of his novel). Hamid explained of Changez: "He is always aware of certain benefits that America hands over to him, benefits that are part of the American corporate culture. At the same time the culture doesn't work for him. He becomes at once ashamed and proud of his background." It's difficult to see how any writer could have captured the conflicting--almost contradictory--feelings so many of us feel about America in these post-9/11 days. Capitalism stinks, yet I don't know of any better system. And democracy? Well, sadly in a democratic society, you get the person you elect. And in these troubled times, too many of us are looking for better leaders than the ones we have. Yet immigrants in the United States are often more accepting, more appreciative of the country than those of us who were born here. Mohsin Hamid brilliantly recreates that love and hate for America, perhaps only the way that someone not born and raised in the USA can. Initially, to be sure, Changez certainly appears to be content with his life in America--for quite a time, in fact, after he leaves his home in Pakistan and enters the United States on a student visa. Changez attends Princeton University (as the author himself did) and subsequently lands a top-notch job with a prestigious company that evaluates other companies, advising them how to enhance the value of their assets. Changez's even got a beautiful American girl who gives him her attention instead of her multiple suitors. Everything appears to be going well--and Changez is getting rich. Hamid is a master describing all these incidents in his main character's life. His writing is fluid, at times almost lyrical, even heavy with sensuality. (Hamid published an earlier novel, "Moth Smoke," in 2000.) Then 9/11, and Changez is changed (no pun intended) in the way that millions and millions of people around the world were forced into a new reality. In a hotel in Manila (where he has been sent by his employer), Changez turns on his television and, momentarily at least, believes that what he is watching is another Hollywood blow-up-everything extravaganza. And then, "As I continued to watch, I realized that it was not fiction but news. I stared as one--and then the other--of the twin towers of New York's World Trade Center collapsed. And then I smiled. Yes, despicable as it may sound, my initial reaction was to be remarkably pleased." Immediately everything in his life is altered. Passing through customs as he re-enters the United States, he is scrutinized as he has never been before. People on the street, even his colleagues, look at him differently. He recognizes an incipient anger in people who regard at him with suspicion. Equally unsettling, Erica, his American girlfriend, goes through her own altered state, brought about by memories of the death of an earlier boyfriend who died of cancer--years before she and Changez met one another. Listless at work and concerned about tensions back in Pakistan (specifically the fear of a war with India), as well as the health of his aging parents, Changez returns home, to Lahore. Eventually, he begins teaching at the university. Ironically, it is in that university context--and not at Princeton--where Changez becomes radicalized, attracting increasing numbers of students to his classes. The entire narrative is told in Changez's voice as he sits in a café and talks to an American tourist like the Mariner in Coleridge's celebrated poem: Princeton, his tortured love for Erica, his prestigious job. And then 9/11. Throughout, the reader is charmed, beguiled, and fearful of things to come. As the author himself has explained to "The Stanford Daily," "The novel is like a conversation much like the world is in conversation. The expectation that a terrible thing is going to happen, speaks for the world today." In an additionally revealing comment in that interview, Hamid explains: "...eople are being overly frightened about the wrong things. Terrorism is a huge problem that needs to be addressed. But forty thousand people die in car accidents [in the USA] yearly." Far fewer on 9/11. American history is one of fear--"moving into new territory...The War on Terror is a misnomer. It is a War on Fear." Perhaps, more succinctly, a war to create fear around the world. These are brave remarks from a bold writer who minces no words. Moreover, in the most telling passage from The Reluctant Fundamentalist, Changez addresses America directly, almost pleading for understanding: "As a society, you were unwilling to reflect upon the shared pain that united you with those who attacked you. You retreated into myths of your own difference, assumptions of your own superiority. And you acted out these beliefs on the stage of the world, so that the entire planet was rocked by the repercussions of your tantrums...." And then Changez remarks about his own situation as a teacher at the university: "When the international television news networks came to our campus [in Lahore], I stated to them among other things that no country inflicts death so readily upon the inhabitants of other countries, frightens so many people so far away, as America." Are American readers ready for Mohsin Hamid's conversation with the world? Is anyone in America reading The Reluctant Fundamentalist? Fortunately, there are signs of increasing awareness. The novel has appeared on the list of best-sellers in "The New York Times Book Review," and it's selling well on Amazon.com. Besides the United States, other editions of the novel have appeared in England and in India. Though no optimist, I take these as encouraging signs. Perhaps fiction is the door through which Americans will begin to understand what happened to them. Charles R. Larson is Chair of the Department of Literature,

American University, Washington, D.C., USA

|

|