Book Review

A Country Inside A Writer's Head

Syed Badrul Ahsan

Isabel Allende, like so many of her compatriots, left her native Chile long ago. Unlike many of them, however, she has kept returning to her country, coming away every time with newer insights into the society and politics of the land. As a writer, indeed as a novelist, Allende has known enough about Chile, about herself, to convince herself of her identity. She knows, certainly, that her second marriage, to an American, was guided more by the temptation of making a home abroad than giving expression to romantic passion. For all that practical demonstration of reality at work, though, Isabel Allende has remained the Chilean she has always been. For her, Chile is something more than physical geography. It is an image, an idea she has constantly nurtured and shaped and reshaped in the mind. And that is how she has reinvented the old country.And well she might. As a cousin of the murdered Salvador Allende, she has watched politics operate at close quarters, has survived the ferocity of Augusto Pinochet's goon squads, much like Michelle Bachelet, the current president of Chile. But what makes My Invented Country a proposition different from the general run of memoirs is the light-heartedness which cloaks the seriousness of Allende's thoughts. She resorts to banter, to healthy, self-deprecating humour to portray a people with whom her political umbilical links cannot be severed. Read the beginning of her tale: "Let's begin at the beginning, with Chile, that remote land that few people can locate on the map because it's as far as you can go without falling off the planet." The premise of her narrative is thus laid out and what happens as the story rolls is a fascinating exposition of images that dot the many layers of the work. She has time to glimpse the elongated country, as she calls it, through the poetry of Pablo Neruda besides rushing through descriptions of the frenzied childhood she has been through among a vast train of grandparents, uncles, aunts, cousins, et al. Whatever else you might spot in that narration, boredom is something that will not strike you. As happens in so many other countries across the globe, bureaucracy impacts on the health of the average citizen. It can, in Chile, descend to ludicrous depths, even where the point of discussion happens to be the death, or otherwise, of an individual: "Even if (a citizen) throws a tantrum to prove that he hasn't died, he is obliged to present a "certificate of survival"'; that "recently, a busload of us tourists crossing the border between Chile and Argentina had to wait an hour and a half while our documents were checked. Getting through the Berlin Wall was easier. Kafka was Chilean." Here one can also see the writer's careful staying away from rancour. If anything, it is the amusing aspects of life, a quality that must come to every writer, that constantly grabs her attention. She advises the foreigner who might be at risk of failing to comprehend the speech of Chileans, who speak, as Allende informs us tongue-in-cheek, at least three official languages (the educated speech of officials, the colloquial language of ordinary people and the indecipherable and endlessly changing speech of young people): "The visiting foreigner should not despair, because even if he doesn't understand a word, he'll see that people are dying to be of help. We also speak very low and sigh a lot." For all her seemingly unserious way of observing the world around her, though, memories of 11 September 1973 when Salvador Allende's government was overthrown in a violent military coup run deep. For Allende, for tens of thousands of other Chileans, the coup was a decisive point. It pitted them against organised villainy and then forced them into exile, external as well as internal. "Friends and acquaintances," Allende writes, "began to disappear; some returned after weeks of absence, with the eyes of madmen and signs of torture. Many sought refuge in other countries." In exile in Caracas, Isabel Allende and other Chileans sought to recreate the old Chile of the happier days. They came together to listen to the music of Violeta Parra and Victor Jara and to give one another posters of Salvador Allende and Che Guevara. Chile turned into part of memory and took rebirth in Isabel Allende as the land of the poetic and the poor. Chile lives, as her grandchildren keep telling her, as a country inside her head. She agrees; she whispers, to no one in particular: "Only the landscape remains true and immutable; I am not a foreigner to the majestic landscape of Chile." S. Badrul Ahsan is executive editor, The Dhaka Courier.

|

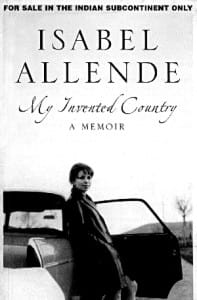

My Invented Country: A Memoir by Isabel Allende; Flamingo/HarperCollins Publishers; 2004 |