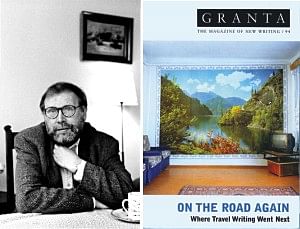

London, Ian Jack and Granta magazine

Khademul Islam

"Can you come in on Friday morning at ten am?" Ian Jack, editor of Granta, had emailed me on July 11. The address: Hanover Yard, Noel Road, behind the Queen's Pub. A few days later, however, emerging from Angel underground station into the shadows cast by tall buildings, I was stuck. Where was Noel Road? It had been five years since I had last been in London, and was still getting re-acquainted with the business of getting around the city on my own. A turn ventured at an alley whisked me away from the gloom to a sunny street. Dhaka sunlight! This was the first time I had been to England in the summer, and the light was a continuing marvel. A woman pointed out Noel Road, and in a few minutes I was at the pub. Behind it, at the end of a cul-de-sac, was a neat-looking, white house. It was very quiet here, no crackle of Polish or any of London's newer immigrant accents. Very English. The sign by the door said 'Granta' in neat capital letters. It was nice inside. A good-sized reception area with light streaming in from large windows. Nothing like the lit magazine digs in Martin Amis's novel The Information: "The offices of The Little Magazine were little offices...Evicted often and forcibly from this or that blighted flatlet, it sometimes lingered in the dark behind the beaten door like a reeking squatter in his vest." I was directed upstairs to the second floor, to Ian's large corner room. Books and papers on tables and window shelves, but not too much of them. Perhaps, as he had written once in The Guardian, Ian had actually tossed out a few old books. I remembered the article because of its Larkin quote, "Books are a load of crap." Granta was fond of Philip Larkin. On the cover of the Family issue they had dared to print Larkin's famous line about family, along with its four-letter word. Ian, in jeans and with his white shirttails out, got up from his computer desk and shook hands. He moved us to another table. His face looked somewhat familiar but I couldn't quite place it then. Ian Jack has been the editor of Granta since 1995. England's leading literary magazine (or perhaps on both sides of the Atlantic) was started by students at Cambridge university in 1889 and named after a river there. Till 1979, when under Bill Buford Granta radically transformed itself into a serious literary journal devoted to "new writing," it had been a student magazine purveying "jests... (and) pastiches of Kipling," as Ian wrote in the 2004 Jubilee issue. When Buford left for The New Yorker magazine in 1995, Ian was handed the keys to house. I came to read Granta late. The British Council library in Dhaka didn't have it, and anyway I was more drawn to American books and writers, which I saw as a counterpoint to British fustiness. The first Granta I read was mailed to me in America by my sister. Number 34, 1990, Death of a Harvard Man. Granta at first felt strange, its writing and writers of a different order and key. Without a subscription, it was difficult to get hold of in the USA, but I would chance upon the occasional volume. The one on Family, of course, the Vargas Lhosa one, Best of Young British Novelists '83, Food, Fifty, London, the one on India. Granta led me to writers like James Fenton, Martha Gellhorn, Martin Amis, Iain Banks, and later, Decca Aitkenhead. It published radically different kind of travel writing and photo essays; its prose and themes occasionally seemed viscerally closer to the Third World I called home than its American counterparts; and it could still jest, as demonstrated by Michael Mewshaw's funny piece on Anthony Burgess ('Do I Owe You Something', Autumn 2001). By that year I was a subscriber. But shortly afterwards I returned to Bangladesh, where supply was non-existent. My brother got me a year's subscription, but only one issue made it through to Dhaka. And the British Council library still didn't stock it. Later on in my trip, though, fate intervened. Going through used books at New York's landmark Strand bookshop, I came across Granta back issues, a buck a copy. I wish I could have picked up the whole lot, instead of having to choose the seven or eight due to airline weight restrictions. Back in Dhaka, I have read a whole lot more of Granta writing. Still, there are many issues I know nothing about. Our chat started off slowly, mainly because -- well, literary editor of an English-language newspaper from Bangladesh, I am quite sure Ian hadn't seen the species before. He began by asking about the old port bungalows in Narayanganj, and about the Rocket steamer to Barisal. He had once, he confided, wanted to write on steamboats in the subcontinent. He mentioned Faridpur and Comilla. Surprised, I asked if he had been to Bangladesh? Turned out yes. Turned out Ian had been a newspaperman, in fact, The Sunday Times's correspondent in New Delhi. From 1991 to 1995, he had been the editor of The Independent on Sunday. It was then that the penny dropped, why his face had seemed familiar. It was the accompanying photo, a younger Ian in white kurta pyjamas, to his piece in the India: The Jubilee Issue of Granta. I was nonplussed. I had read some of his articles in Granta and The Guardian, and true, there were references to India in them, but somehow I had never picked up on the fact that he had been a foreign journalist in Delhi. Or if I had, I had forgotten it in the intervening years. Journalism, then, accounted for his writing style, which was direct and un-donnish, as if he had taken to heart author Elmore Leonard's dictum: "Try to leave out the part that readers tend to skip." Birds flitted outside the windowpanes. London birds. In Dhaka I no longer heard the kokeel I used to in the mornings. Too much apartment construction, too much leveling of green. Plus the growing army of the dispossessed on the streets. Granta, Ian said, had evolved into the magazine it was now because standard definitions of what constituted literature didn't apply any more ("literature, whatever that is"). With the old formulations suspect, almost by default, then, any literary magazine worth its salt had to venture forth into newer areas, explore newer forms. This trend, a distinctive kind of nonfiction -- memoir, history, travel, and a superior kind of reporting - had been strengthening in the writing published in Granta under Ian's aegis. What did he look for, I asked. "Good writing," he answered. He didn't go beyond it, it was something obvious to him, rather like the judge who said that he couldn't define what pornography was but that he would know it when he saw it. Granta had steered clear of structuralism or postmodernism and any of the other isms, that "we haven't gone near that, wouldn't know what it was," and that hindsight was showing that perhaps they had been right to do so. He returned again, with relish, to what basically Granta was intent on publishing: "the long, involved, searching essay." "Reportage." Writing had to bring fresh news, fresh perspectives about us, about the earth. Mere technique wouldn't do. There were writers who had a lot of technique, a lot of polish, but had really nothing new to say, nothing fresh to give, and so...here he trailed off and looked up at the ceiling. I asked about "writers from the margin," whether Granta should publish more of them. Say, from Bangladesh. Here Ian squirmed a little in his chair. I sympathized silently. No editor, least of all of a literary magazine, should have to guarantee publication based on degrees of marginality alone. "Well, if it's good writing," he said finally. Fair enough! How did they choose a theme for each issue? Well, mostly at staff meetings. Sometimes it just came to them, as when after 9/11 they brought out the What We Think Of America volume, chiefly "because the 9/11 theme was being done," no pun intended, "to the death." Much more rarely, it happened that a writer would submit an outstanding piece, and then Granta would get other writers to "build around it." And so he roamed over other related topics: the practice at Granta of working closely with their writers, the "retail" book publishing business in Britain, the latest issue of Granta (On The Road Again: Where Travel Writing Went Next), the difference in money between America and England in terms of magazines and publications. "Editors here in England," he said with a self-deprecatory grin, "nobody gives much of a damn, I mean we are okay, but it's over there, in America," where they commanded power and money. For obvious reasons, I didn't bring up the topic of editors in Bangladesh. But there was also good news. Granta, previously owned by Rea Hederman of The New York Review of Books, had been bought (saved was more like it) last year by Sigrid Rausing. Sigrid is one of the billionaire heirs to the Tetra-pak (the cardboard cartons for liquids) fortune, and she was interested in expanding Granta Books, the journal's book publication arm. Later, in New York, over lunch, I asked Kim about Sigrid. "Oh, she's huge in funding for human rights," Kim, who herself works for a non-profit, replied. "Her foundation does a lot of good work. Why, are you going to meet her?" "Jesus, no, no. Somebody mentioned her very favourably, that's all." Before leaving, I gave Ian a copy of The Daily Star Book of Bangladeshi Writing. He accepted it gratefully, and thumbed through it, peered at the Contents, looked at the cover. "This was published in Bangladesh?" "Yes." He took me over to meet Fatema Ahmed, who is the managing editor of Granta. Her folks are originally from Bangladesh. She told me about a novel by Tahmina Anam (who is the daughter of our editor Mahfuz Anam, I informed them to their surprise), due to be published from Britain next year. Fatema had read the manuscript. And? "It's good." Ian then affably padded downstairs with me, saw me to the door. I shook his hand and stepped outside. It was downright hot. Was this London, or Dhaka... Khademul Islam is literary editor, The Daily Star.

|

|