Short Story

Goodnight, Mr. Kissinger

Part-I

Kazi Anis Ahmed

I.

The first time I met Henry Kissinger, I was shocked at how frail he appeared. Of course, "met" is a strong word when you are a waiter. But waiters in restaurants of a certain elevation, like butlers or barbers of another era, enjoy a strange though controlled intimacy with the men they serve. At a place like The Solstice, it is almost expected for a good waiter to get past the menu with repeat visitors. Once in the middle of a conversation with a silver-haired lawyer, Kissinger was groping for the name of the capital of Tajikistan. It was a delicate call; I took a chance: Dushanbe. "What is your name?" Mr. Kissinger asked me with slight bemusement. "James, sir. James D' Costa. "Where are you from?" "Bangladesh, sir." "A James from Bangladesh? An unlikely name for a Bangladeshi, isn't it?" "It's an unlikely country, sir," I replied as I swept away the crumbs from the thick white table-cloth. Encounters with the famous and the mighty was one of the great perks of my otherwise often tiring job: politicians, movie stars, authors, sports heroes, socialites. Just the week before meeting Kissinger, I had witnessed the daughter of a real-estate tycoon storm out in tears over a break-up. A month before that I had to find a spare pair of trousers for a druggy star who had soiled himself in the men's room. I was moved by the graciousness of Gregory Peck, and charmed by the sweetness of the Queen of Jordan. Once I pulled Harvey Weinstein away I am an exceptionally big man for a Bangladeshi - when he struck a young director who had crossed him. Yet, somehow the little repartee with Kissinger felt like the highlight. When I brought the check to Kissinger, he asked me, "So how is your unlikely country doing these days?" "Quite well, sir," I replied, trying to stay neutral. "It can't be doing that well if you are here, can it? How long have you been in America?" "Just two years, sir." "I hope your country isn't still a basket-case for the sake of those who are stuck there," said Mr. Kissinger, as he wrote in a fat sum for the tip. Clearly, I had not been forgiven for Dushanbe. But the insult was excessive. The dessert knife, still on the table, flashed before my eyes. Kissinger's neck was soft and crumply enough that I could have pierced it with a blunt instrument. I have always been given to sudden and extreme bursts of rage, though I try not to act on them. The last time I did, I had to leave the country. I removed myself from the scene with a brusque "thank you," leaving the farewell ritual to a smooth-faced actor amenable to my bullying. II.

As far as the American immigration service is concerned, I am a political refugee. The real circumstances of my departure are of course more complicated. I used to be an English teacher at a private college in Dhaka. One would not expect a character like me to become a teacher. I harked back to British times when tough guys became teachers, and ran gymnasiums to train young anti-colonial radicals. I doubled up as the games teacher for my college. Not the pot-bellied, whistle-blowing kind. I taught the boys how to dodge and tackle, taking hard falls with them in the rain-sodden field on summer afternoons.I felt free to egress into unnecessary territories. Anytime the faculty had a new need not something as grubby as a salary-increase but a new line of acquisitions for the library or an expansion of the common room, I would lead the negotiations. I chided the peons when they slacked off on keeping the bathrooms and corridors clean. I bullied the bullies among the students. I could have asserted myself in a bigger arena, but felt content with the little theater of my college. I enjoyed scolding socially well-placed but negligent parents. In addition to temperament, I was helped in my subtle transgressions by sheer physical size. I was big not just for a Bengali, but for almost any nationality. I could crack open a hard coconut shell with the back of my fist. I used this trick to awe the newcomers, and to intimidate any challengers. I should have known that my predilections destined me for trouble. A student, whom I had failed, begged first for re-grading, then re-examination. Then he grew bolder, offering veiled threats. Violence has become so common in Dhaka that everyone knows a two-bit goon, and feels free to lean on that assumed advantage. I slapped the boy hard and told him to focus on his studies. A few days later, I found a trio of gold-chain-wearing clowns outside the college gate, leaning against their 100cc Japanese bike as if it were a Harley. I found their posture comic, and paid no heed to their hard stares. But a few weeks later when I was returning home, they fell upon me without any warning or preamble, just as I turned the corner onto the dark alley leading to my house. I took a cut to my chin, but managed to wrestle away a bicycle chain from one of their hands. The student was the slowest to escape. I chased him down and with one metallic swish from behind caught him across the face. I should have stopped right there; but I could not forgive a student who would dare raise a hand against a teacher. The fact that I had acted in self-defense, even if excessively, was completely overlooked in the ensuing uproar. A few students began a boycott of my classes, and a few parents pressed for an investigation. My defense grew weaker as the boy, now the victim, languished in a hospital. Within a week, no students attended my classes. The authorities asked me to take leave pending an investigation. Old stories about my prowess and vigilance circulated with sinister exaggerations. The boy's parents pressed criminal charges. I did not have the appetite for the legal fight, nor for the humiliations needed to resolve the issue out of court. I managed to secure an American visa, and upon landing filed for asylum. It helped that I was a Christian with a record of secular activism from a country growing ever more (religiously) radical. III.

When I say I am given to sudden rage, it is not entirely accurate. I have always lived in a state of seething rage. The epicenters of my rage shifted over the years. Targets receded while new obsessions bloomed. As a child, if the cooking was not to my liking, I would hurl the bowl of curry at the wall and watch the yellow sauce dribble down our much-stained wall. In a developed country they might have submitted me to some form of treatment or counseling. Back home I received vigorous thrashings from my father, but I lost him too early in life to know if his admonishments might have made a difference.During the war of liberation I was only nine. My father, pastor of a small church on the outskirts of Dhaka, was shot dead by the Pakistanis. The soldiers invaded our house early one morning. Somehow the army skipped our town in the first days of war, when Dhaka was massacred. But a couple of months later, they entered our town blaring the message that anyone who lived peacefully and cooperated would be unharmed. The next morning they came for my father, the first operation in our town. I remember that ten or twelve soldiers had entered our little compound. I imagine more surrounded the house, and guarded the arched gateway of our very old house. My father came out to the verandah, already bent in submission, appeasement dripping from his voice. That's what I remember most vividly. The image of my father on his knees, shirt open, pleading for his family. My mother and I watched from behind a door. My mother held my one-year old brother to her breast. The child, sensing disorder, began to bawl. Luckily, the soldiers were not interested in us. They had come specifically for my father, who they believed was aiding insurgents. Having ensured that there were none hiding in our house, they left us alone. One soldier stood by the gate, under the old Arjun tree, with a leering smile on his broad square face. In a moment like that your comprehension can transcend your age and become universal. I knew even at that age, and in that moment, that the soldier was not smiling with malice, but out of idiocy. He fired suddenly at a goat that leapt out of the vegetable patch at one end of our compound. The major leading the operation blasted a series of expletives at the idiot soldier and ordered him out. Then he turned and barked another order, and my father was shot ten or twenty times, I can't remember, even after his body had gone still on the ground. Many details of that morning are no longer vivid in my mind. I don't remember if it was a cloudy morning, or which neighbor was the first to rush over once the soldiers left. What I remember vividly is the shaking, kneeling figure of my father, and the smiling face of the idiot soldier. Where is he now? I wondered as I grew older. What if I went to Karachi or Lahore some day, and found him behind the counter of a store? My unstable moods, in the absence of my father, grew more volatile for a period. Especially in my teenage years, I got into scrapes constantly. I spent almost as much time in suspension as in class. I daydreamed, not of girls, or football, or cars, or anything teenagers commonly fantasize about, but of revenge. I drafted elaborate plans to execute the killers of 1971. It would not be necessary to kill all the culprits; I required only symbolic justice. Yet, justice was the only thing that my country failed to deliver. I became involved in secularist politics after democracy was restored in the early '90s. I organized awareness-raising events in small towns. But, to my dismay, once in power, even the liberals succumbed to compromise. Eventually the killers and collaborators became ministers. I gave up on wider political work, and became increasingly concerned with upholding vestiges of order and dignity in the immediate and small arena of my college, until, of course, things went too far. IV.

The move to America seemed to calm my spirits. Or, my shaky legal status in an alien land had a restraining effect on my temper. We had sold the old family property to raise the money for my passage. I blew?? much of that fund on a rental deposit for a one bed-room in Sunnyside, Queens. My brother, who didn't mind selling the house for my safety, was irritated when he heard of this move. The few contacts from home I met, and later avoided, advised me against it. But having spent the first few weeks with six young Bengali taxi-drivers in a two-bedroom, I was sure I wanted my own space. I had never lived alone before in thirty-seven years. I couldn't believe how good it felt.I liked being alone when I woke up, and when I went to sleep. I could see living alone for the rest of my life. I had loved girls, and I had been loved back. But the one girl I might have married, I lost for reasons I still don't understand. I felt no strong need for companionship at this time. I worked one long shift from noon to ten at night. I liked having much of the mornings to myself. To go sit at the diner by the station, with a paper, made for a morning hour more delicious than any I had known before. I liked the smell of coffee, and I liked how in this country they topped it up endlessly. While my work was not easy, I had it easier than many of my countrymen. I could not pass by any Bangladeshi fruit-seller on winter mornings without a shiver of pity for them, and thankfulness for my luck. My move up the restaurant ladder to The Solstice was rapid, thanks mainly to my English, and general quickness. I enjoyed learning about the great wines of the world the difference between a Petrus Pomerol 1998 and an ordinary $100 Merlot appealed to some arcane aspect of my temperament. I loved the elaborateness of our accoutrements, the hierarchy, the rituals, and the art of effacing it all into a seamless, effortless performance. Here, finally, was a civilized order. I was never desperate, like millions of my countrymen, to leave Bangladesh. I had never given serious thought to emigration, never explored any such options. Yet, trading the chaos and violence of Dhaka for the relative calm and order of New York felt like a boon. My new city, like my place of work, offered me a world of rules. In return, I needed to keep my overdeveloped sense of dignity under check. Surprisingly, this task came as a huge relief. No longer did I have to measure every smile, look, or gesture, nor constantly defend myself against the slightest omissions of respect. I felt no great longing to go back to Dhaka, even for a visit. Of course, I missed aspects of Dhaka. I missed the kaal boishakhis that heralded summer with sudden and terrible lash of winds and hale. I missed dal puris with hot tea at the stall by my college on foggy winter mornings. But, on the whole, I was happier in my new life. The owner of a Bangladeshi restaurant in Astoria approached me at regular intervals to teach at a public school loaded with Bangladeshis. The man was a busybody who took an interest in community affairs. "The boys and girls need a Bangladeshi teacher, a role model. Someone strong and good in English." Sometimes he came to see me with sidekicks to add weight to his appeal. "Surely you know why I left home?" I said to dissuade the man. "People there always overreact and exaggerate," said the man gallantly. "I pay no heed to rumors." Clearly, they were desperate for a good teacher. But I was not moved by their need or flattery. To accept their offer would mean getting drawn into the community, and the politics and issues from home. I did not wish to have any old feelings stirred up. But, I should have known that it is not easy to leave worlds behind. Just when I thought I had fully bulwarked myself against my past, it ambushed me from a completely unexpected direction, in the unlikely figure of Henry Kissinger. Like all educated Bangladeshis, I held Kissinger culpable to some degree for the genocide that occurred in my country in 1971. I knew that he did not order it, but I also knew that he did nothing to discourage his Pakistani clients, though he wielded enormous influence on them. These were issues I had gladly left behind. Yet, suddenly now the issue was palpably before me, demanding to be fed and humored. Kazi Anis Ahmed is director of academic affairs, University of Liberal Arts, Bangladesh.

|

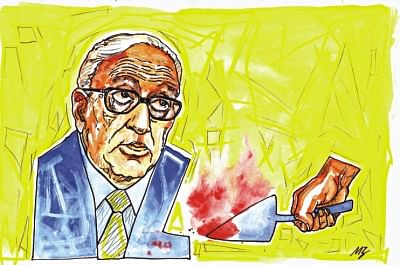

artwork by mustafa zaman |