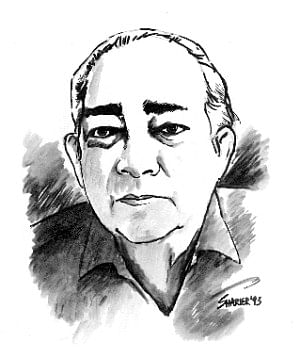

Remembering Syed Mohammad Ali on his birthday

Syed Muazzem Ali

Syed Mohammad Ali, one of the outstanding journalists of the country, and my beloved Boro Bhai (eldest brother), was born seventy-seven years ago this day. In our middle class families, Boro Bhai has a very special position; he is semi-friend, semi-confidant, and semi-guardian. I remember his visits home from Dhaka, where he was completing his Masters, to Gopalganj, where our father, Syed Mustafa Ali, was posted as Sub-Divisional Officer in the early fifties. He was affectionate, and very gentle and polite to everyone in the family, older or younger than him; yet we were too young to fully interact with him.From those early days his desire was to be a journalist, and he used to write in different newspapers. After obtaining his Masters degree in English from Dhaka University in 1951, he began pursuing his dream profession on a full-time basis. In those days, the life of a journalist was uncertain and naturally, our father, a member of Assam Civil Service, would have liked his eldest son to follow his own footsteps, and that of his younger brother Syed Murtaza Ali, into the civil service. Boro Bhai had no such interest. He decided to move to Karachi, and joined the Evening Times as an Assistant Editor. Thereafter, he joined the prestigious daily Dawn. In 1953 he left for London, where in addition to receiving professional training, he worked for BBC and the News Chronicle. It was after his return from London in 1956 that I began to know him closely. Whenever I entered his room I would find him bending over his small portable typewriter with a cigarette at his lips and a cup of tea on the small side table. Sometimes he would give me a neatly typed page, which he had just written and ask me to read it. As a seventh grader, I may not have fully comprehended the political connotation of the piece, but I appreciated its simple and lucid English. I do not remember having to open the dictionary too many times to check the meanings of the words he had used. Boro Bhai was a very popular person, and many of his friends, of both sexes, would telephone home for him. He taught us how to receive phone calls and take down messages. To us he was a Pucca Sahib, who spoke softly, dressed smartly, and conducted him with great honour and dignity. At that time, he was working in the Pakistan Observer, and whenever he had time and money, he would take us to restaurants like Casbah, Gulsitan, or La Sani. If he did not have enough money, we would go to "western style" dining room at the Fulbari railway station and have a four-course meal for two rupees each. The purpose of taking us out was to give us a break and, at the same time, teach us table manners. I remember those days eating in those "western style" restaurants meant eating with fork and spoon. One day Boro Bhai politely pointed out to us that an Englishman would only use spoon for taking liquid food like soup or porridge and that we should switch to eating with fork and knife. We mastered that quickly, but it was extremely difficult to use them as noiselessly as he did. Boro Bhai was obviously interested in increasing the sphere of his activities. By the time I went to college, he had left for Lahore to join the Pakistan Times as its Assistant Editor. The management of the Pakistan Times soon nominated him to represent them at Asia Magazine, a colourful Sunday paper, and Boro Bhai left for Hong Kong in 1961. That was the beginning of his three-decade long sojourn in South East Asia. From Hong Kong he moved to Bangkok to work as the Managing Editor of Bangkok Post, then on to Singapore as the Roving Foreign Editor of the New Nation. He returned to Hong Kong as the Managing Editor of the Hong Kong Standard, and then moved to Manila as the Executive Director of the Press Foundation of Asia (PFA). Finally, as the Unesco Regional Communication Adviser for Asia, he was based in Kuala Lumpur. Boro Bhai had lived abroad for the major portion of his life, but his heart was firmly rooted in Bangladesh. Whenever and wherever I met him during that periodin Warsaw or New Delhi, where I was posted, or in Hong Kong or Kuala Lumpur, where he was basedhe would invariably talk about Bangladesh and how the country was doing under most trying conditions. When natural disasters would strike Bangladesh he would exclaim: "Oh God, what have we done to deserve this?" During the liberation war he was based in Singapore and played an important role in building public opinion in favour of our cause by setting up friendship committees in Manila, Singapore, Kuala Lumpur, Hong Kong, Tokyo, and Bangkok. These committees included local writers and journalists and intellectuals from those capitals. At that time, there were very few Bengali expatriates living in that region. After the independence of Bangladesh, he came to Dhaka and stayed for a few months. On the basis of that experience, he wrote the book, "After the Dark Night," frankly describing the newly independent country's problems and prospects without any fear or favour. He highlights the superb character of Bangabandhu, his great love for Bangladesh and his people, his generosity and indomitable courage, and the humane treatment that he extended to his political opponents, and even to those who had collaborated with the Pakistani occupation forces. The book is immensely interesting and gives the reader a glimpse of the major challenges that Bangladesh faced at the critical initial years of its nationhood. Incidentally, the book is cited as a reference book on Bangladesh in several universities in the United States. Boro Bhai, during one of his trips to New Delhi in the late eighties, mentioned to me that after his retirement from the Unesco, he would like to return to Bangladesh and do something worthwhile for the country. Frankly, I was a bit apprehensive whether he and Nancy Bhabi, a Chinese-origin Singaporean national, would be able to adjust to life in Dhaka, and I was also worried about his health. He was contemplating bringing out a first class English daily from Bangladesh. While welcoming the idea, I expressed my concern about his health. Boro Bhai smiled and said, "I can easily spend the rest of my life in any South East Asian capital and survive on my Unesco pension, but instead of wasting my time, let me do something worthwhile for my country." Boro Bhai moved to Dhaka in 1989, and initially joined his original paper, Bangladesh Observer as its Editor. He finally got the license to start a newspaper and The Daily Star was born on January 14, 1991. His personal column "My World," which revealed his depth, forthrightness, determination, grace, and charm, was very popular. Soon The Daily Star emerged as a leading English daily in the country. I moved to Dhaka in mid 1992 from Bhutan, and this gave me and my wife Tuhfa and our two sons Nausher and Nageeb the opportunity to know Boro Bhai and Bhabi more closely. A visit to their flat in old DOHS was a rewarding experience for all of us. Many weekends, and on social and religious occasions, he would join other family members at our flat at Kahkeshan in Bailey Road. He was particularly fond of Sylheti delicacies like shatkora and birni rice that Tuhfa used to prepare especially for him. We lived on the top floor, and it was difficult for Boro Bhai to climb those stairs, yet his love and affection for us made him to go through the exercise. Boro Bhai was an old school journalist who believed that trust and confidence of people must be maintained at all costs. Once he narrated to us how the Chinese Foreign Minister Marshal Chen Yi had, at the end of a conversation in 1964, suddenly mentioned that the conversation was "off the record," and had thus ended his golden opportunity of publishing a sensational piece at the height of Cold War. Despite the obvious temptations, Boro Bhai had maintained his journalistic ethics and had never disclosed the contents of that conversation. Sometimes he would meet our national leaders and we would pester him to tell us what they had talked about. He would give us his usual disarming smile and change the topic. At family gatherings he would remind us that his principal allegiance was to his readers and that we should keep it in mind before discussing any national or international issues with him. If the event went past his normal retiring hours, he would excuse himself by saying that he had "to bring out a newspaper the next morning." We lost Boro Bhai at the prime of his professional life. He was only 65 years old. Whenever I think about his death, I remember how suddenly and how fast he was taken away from us. In his death, the country lost an outstanding son of the soil and we lost our friend, philosopher, and guide. Just weeks earlier, Boro Bhai was admitted to a local clinic in Dhanmandi for a minor surgery. When Tuhfa, myself, and Nancy Bhabi met his doctor, the latter reassured us that the surgery itself was minor. However, in view of his general health condition, he apprehended that Boro Bhai might need blood transfusion after the surgery. Since it is always hazardous to take blood from professional donors, he enquired if my younger brother Syed Iqbal Ali and I could drop by the pathological laboratory for a blood test for that eventuality. After the test, the doctor confirmed that our blood group was the same and asked us to be in a state of readiness. Iqbal quipped, "We may not be as famous as Boro Bhai but at least we have the same blood." The surgery went off well and he did not need any blood transfusion, but doctor sent a sample for biopsy. The worst fear came true; it was diagnosed that Boro Bhai was suffering from lung cancer. National Professor Nurul Islam told us that he should be sent abroad quickly for further treatment. We were in utter disbelief. Nancy Bhabi told us not to divulge full details to Boro Bhai and to persuade him to leave for Bangkok soon. His first reply was that he couldn't leave in such short notice and that he needed some time to make necessary arrangements at his office. He was finally persuaded, Thai visa was arranged, and our cousin the late Hedayet Ahmed, who was heading the Unesco regional office in Bangkok, made all the hospital arrangements. We saw him off at the airport within two days of his diagnosis. Before leaving for Bangkok he went to The Daily Star office and spent some time with his colleagues. In his last piece dated October 1, 1993, he wrote under the caption, My World in a Suspended Animation: "As I will be going on two to three weeks leave for my regular medical check-ups, a bit of rest and an overdue holiday, in that order, probably from this afternoon, the column will not be appearing for the next three Fridays. During my absence, Executive Editor Mahfuz Anam will be in charge of the paper as the Acting Editor." His condition deteriorated fast, and Hedayet bhai asked me to reach Bangkok immediately. Our youngest brother Syed Ruhul Amin also rushed from Zambia. Boro Bhai never knew that two of his loving brothers had come to see him. He was already in a coma, and passed away on October 17, 1993. After his death, his friends in Kuala Lumpur brought out a compilation of all the installments of his "My World" column. In Dhaka his autobiographical novel "Rainbow Over Padma" was published. The central character of the book, Rafique Anwar, and his Singaporean wife Sara bear striking resemblance to our very dear Boro Bhai and Nancy Bhabi. Anyone interested in our politics and personalities should find this book immensely interesting and useful. It is a beautiful blend of personal narrative and a political commentary. The central character discusses the political situation of Bangladesh frankly and expresses his deep disappointment at the way things were moving in the country at that time. It is a narrative filled with Boro Bhai's patriotism. I cannot resist the temptation of quoting a statement of the central charactera statement that is as valid today as it was when the book was written: "We must revive the vision and idealism that gave birth to Bangladesh. I cannot believe that we do not have even ten million Bangladeshis, no more than ten percent of the total population, who cannot rise above their personal greed and lead the nation out of the valley of despair. Son, we must give them a chance. Otherwise we have no hope for Bangladesh." It is difficult to pay tribute to one's elder brother as the thin line between our private and public life often gets blurred. I remember our late father was so proud of his eldest son that he used to tell us jokingly: "If I put Khasru (Boro Bhai's nickname) on one side of the scale and the rest of you on the other, his side would be heavier." Father was obviously referring to his eldest son's qualities and not his body weight. Father also had infinite confidence in his eldest son and Boro Bhai more than met his share of responsibilities. Our father, an honest and upright civil servant, had very few material possessions, and after his retirement from service, it was difficult for him to maintain our large family with his meager pension. Boro Bhai provided regular sustained financial support. Even after we all started working and after our father's death, he continued to send money to our mother. When I recalled his generous support to his parents and the family, Boro Bhai reminded me that our father had to abandon his studies, just months before his MA examination, in order to join the government service and support his family after the retirement of our grandfather. Then he smiled and said, "After all, I did not have to leave my studies to support the family like our father did." It was so typical of Boro Bhai to underplay his contributions on any issue, public or private. Boro Bhai will be remembered for his sterling qualities and his contributions. The Daily Star was his last contribution and here I must gratefully recognize the untiring efforts of Mahfuz Anam and all his colleagues for maintaining the high standard of the paper. Today The Daily Star can legitimately claim to be one of the leading dailies in the South Asian region. On his birthday, I pray for the salvation of our dear Boro Bhai's soul. Syed Muazzem Ali is a former Foreign Secretary of Bangladesh.

|

|