Short Story

The Daughter-in-law's Vote

Krishan Nambi

(translated from by V. Surya)

Tomorrow was the election. A two-way contest between the Cat and the Parrot. Parrot candidate Veerabaagu Konaar and Cat candidate Maariyaadum Perumaalpillai were giving their very lives to the effort. The town stood riven in two.Pillaiyaar Temple Street in the Brahmin quarter, full of cooks and temple attendants, was the Parrot stronghold. Veerabaagu Konaar supplied milk on credit to several families in that fortress. Meenakshi Ammaal had a cow of her own. From every milking, she kept a fourth of a measure for household use and sold the rest, after diluting it judiciously with water. For cash, of course. If anyone wanted credit, there was always that wretched creditor Veerabaagu Konaar, wasn't there? Meenakshi Ammaal wasn't exactly poverty-stricken. She was the owner of the house in which she lived, and of sixty-six cents of wetland at the end of town. Her husband, the taluk office peon, who had died some years ago, had made over to her the deeds to this property. Ramalingam was their only son. A harmless fellow whom government gave his father's job out of pity. And Meenakshi Ammaal had got him married as well. In her doddering old age, she would need a daughter-in-law, wouldn't she? Though Rukmini was a wisp of a girl, she wasn't one bit a shirker. From early dawn, when she would sprinkle the house-front with cow-dung water and make the daily kolam, she scrupulously carried out all the chores until bedtime. As for cooking, there was fine aroma in her very touch. (Though mothers-in-law are always pointing out some fault or shortcoming, it's all in the cause of their daughters-in-law's progress, so that they get better and better at everything, isn't it?) Rukmini also knew how to milk a cow very well. Milking can make your chest hurt, that's what the neighbour-women said. But then, so many people say so many things. One mustn't let it in one's ears. Nor should one make any reply. Why, the very best thing was not to talk to anybody about anything at all. Such were the wise counsels imparted by the mother-in-law to the daughter-in-law on the day the girl arrived. She'd been skinny, then, too...If doctors had examined her, they would have said it was tropical eosinophilia...But why have such an examination done? Those who came to you offering 'I'll treat you! I'll cure you!' will do anything for cash. Now, was there anything Meenakshi Ammaal didn't know? Consider her age! Her ripe experience! Once a child is born, everything will become all right, declared Mother-in-law. After all, there's no need to rush to a doctor just now, as though somebody here is on their deathbed! It wasn't as though Meenakshi Ammaal gave the orders to her daughter-in-law and just folded her arms and did nothing. She, too, had her tasks. Adding water to the milk, measuring it out and selling it, receiving all income (including Ramalingam's salary), counting the cash and locking it away, watching and considering before spending on anything--all these were her exclusive responsibilities. Every day, Rukmini and her mother-in-law ate together. As Meenakshi Ammaal dished out the food, she would recite: A woman adds to her loveliness

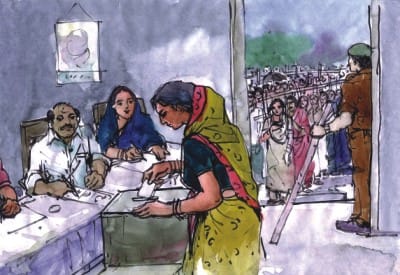

By simply eating less and less. It seemed to Rukmini, as those syllables were being uttered in ringing tones by Meenakshi Ammaal, that that precious maxim had been brought forth by that lady herself, out of her own wisdom. The daughter-in-law had to admit that there was some truth in her mother-in-law's pronouncement that eating too much would make a person put on flesh. (Rukmini herself had only very rarely been driven to snatch a few morsels without anybody finding out.) Without provoking a fight between some daughter-in-law and mother-in-law, the women in town just can't get to sleep each night, can they? Poking right into a girl's mouth they pull out something to take to her mother-in-law, tell tales to each of them in turn and watch the fun! But none of their stratagems worked on Rukmini. It was a big disappointment to them. 'The girl's a voiceless creature!' they said, and ignored her. In the evening gossip sessions outside the front door, when anyone prodded her with the question 'How's the daughter-in-law?', Meenakshi Ammaal would reply, 'She? What about her? She's just fine!' She would then move on to the next topic. With a kind of envy, the women of the town used to say, 'That woman! Who can ever get the better of her?' On the night before the polls, it was not surprising that the dominant note in the conversational concert was the election. Knowing full well to whom Meenakshi Ammaal's vote belonged, one woman mischievously asked, 'Your vote's for the Parrot, isn't it, maami?' 'Ei, di...You know already, and yet you're teasing me, is it?' said Meenakshi Ammaal. 'Wonder who your daughter-in-law will be voting for?' said another, with a wink. Meenakshi Ammaal grew wrathful. 'You girls! How dare you try to split us up with that kind of talk! She and I are one single unit! Mud in the mouth for those who don't know it!' Everyone laughed loudly at that bit of bluster. Polling was a little dull in the morning, but it picked up by mid-day and became very lively. Meenakshi Ammaal was the first to go and cast her vote and return home. On his way home from bathing in the river, Ramalingam was waylaid by party workers, pulled along and forced to cast his vote in wet clothes. After the noon meal, Meenakshi Ammaal was overcome by her usual postprandial stupor and lay stretched out on the floor. Rukmini was in the cowshed, feeding the cow bran-and-water. Watching it eat and drink was Rukmini's greatest joy--a joy that lay outside the boundaries of her mother-in-law's authority. 'Carcass! Heap of dung! However much you eat, your appetite won't come down!' she would say, stroking its forehead tenderly. 'Never think of it as only a cow. It's Mahalakshimi herself! Never ever allow that stomach to go dry. Otherwise the milk will also dry up.' These were Meenakshi Ammaal's standing instructions. 'Cow! Aren't you a woman, too? How is it that only you and mother-in-law don't have to go by that rule of "eating less and less"? Won't you tell me?' Rukmini asked, a fit of giggles bubbling up in her. 'I'm going to vote today. You don't have to bother with such things, of course. Now tell me, will you, for whom should I vote? The parrot's such a dazzling green, so beautiful! To fly like that--oh, how I wish I could! I like the cat, too...but I like the parrot even more.' The level of water in the bucket having gone down, she tilted a pitcherful into it and added handfuls of bran. 'Drink properly, can't you without making a mess?' she said, giving it a little slap on its cheek. Without sucking up the water, it thrust its head deep into the bucket, searching for any lump of oilcake that might be lying up to the surface. Growing breathless, the cow abruptly drew up its face, raised its head and stared around, puffing and panting. At the sight of the circle of wet bran-flecks around its face, she laughed. 'Cow! Listen...it's not enough for you to give milk like you're doing now. You have to go on giving lots and lots when I have my baby! My baby should drink your milk, isn't that so? Will you let my baby drink as yours does--straight from your udder? Like my husband says, I have no breast at all. Just pain in the breast...' Poth! The cow plopped down a gob of dung and squirted enough urine to fill a water pot. With a deft movement of the hands she quickly scooped up the dung, carried it to the dung-pit and dropped it in. She wiped her hands on the grassy earth and picked up the pail and the water pot with the water remaining in them. 'I'm off. Going to vote! I'll come back and let the calf suck.' The udder was hard, swollen with milk. As Meenakshi Ammaal had arranged, some neighbour-women came to take Rukmini along to the polling booth. They were all dressed in their best clothes. Rukmini washed her hands and face at the well and came indoors. 'All right, all right, just smooth down your hair, put a dot on your forehead, and get along,' said her mother-in-law, cutting short her toilette. Rukmini opened the almirah, took out a voile sari dotted with tiny green flowers, and clutching it in her hand, she ran in search of a private corner to drape it around herself. When Rukmini had descended the front steps, Meenakshi clapped her hands and beckoned, 'Here, I forgot to tell you...just come here a minute and go,' she said, taking her into the house. Lowering her voice: 'Remember, don't vote wrong...They'll give you a paper with a picture of a cat and a picture of a parrot. You put the stamp down right next to the cat picture.' It was calm at the polling station. There was a line of women, with many curves in it. Another, straighter line of men. The women's queue was full of colours, and looked like a creeper abundant with flowers, while the men's line resembled a long pole. Rukmini was happy. Very happy. She just loved it all. Here and there on the grounds of that school building stood neem trees, growing and flourishing. She gazed ardently at them. The heat had mellowed. The gently rippling breeze felt soothing and pleasant not just to her body but even more, she realized, to her mind. 'Have I ever been as happy as I am today?' she asked herself. 'Ah! An alisam tree! Over there!' There it was, in a corner, clinging against a well! Was it really an alisam tree? Yes, it was, without a doubt. Rukmini could not contain her delight, she wanted to shout out loud, Alisa tree! O alisam berries! That taste--how different from anything else! At Vempanoor, in those days when she was studying up to the Fifth, how many alisam berries she had eaten! Countless! Vying with the boys, she'd climb the tree with her long-skirt pulled up between her legs, both her thighs showing... The trees were swaying in the breeze. Rukmini had not the slightest expectation of it, but a green parrot with a red beak flew up to that alisam tree, perched on the tip of a branch, and screeched, making the branch swing up and down. How extraordinary! How did this bird get here, now? 'Come, parrot! You don't have to ask for it. My vote is yours. I have already made up my mind. But don't go and tell my mother-in-law. She's told me to vote for the cat. If you come after my baby's born, it'll be wonderful! My baby will also see how beautiful you are, won't he? And when you come, parrot, bring berries for my baby!' When she entered the booth, she found the proximity of strange men embarrassing, and oddly exciting. A pair of dark-skinned, smooth hands moved around on a large rectangular table. There were piles of paper, many red and yellow pens and pencils. She found herself standing behind a screen. Behind her, from outside the curtain came the sound of a woman giggling explosively. Ruku's chest thudded rapidly. She felt an unendurable desire to urinate. Lord, what torment is this! Her teeth pressed hard against each other. Ayyo! It must be milking time! She thought of the cow, its udder swollen and bursting with milk. Why was her body trembling so much? Ahh, the Parrot! A hand grabbed Rukmini's; she turned, startled, saying, 'Who is that?' No one was here...But it was true, anyway, that another hand had taken hold of hers. A woman's hand...her mother-in-law Meenakshi Ammaal's hand! Her hand was taken and moved over to the Cat. Down came the stamp, bright and clear, next to it. Ah! The Cat has Rukmini's vote! Hurriedly she left the polling booth. The women were waiting for her. As soon as they saw her, they laughed; she didn't know why. When she came near, one of them asked, 'Ruki, whom did you vote for, di?' 'For my mother-in-law!' She did not know how it happened, but the words stood up in her mouth and showed themselves. The women gathering around laughed loudly. Rukmini quickly walked away. Her chest hurt more than ever. She had great trouble holding back the grief boiling up within her, and the tears. Krishan Nambi is a Tamil short story writer known for his sensitive portrayals of women.

V. Surya is a well-known translator/academic.

|

artwork by apurba |