Book Review

A Cool-Breeze Novel

Khademul Islam

This is a delightful, hilarious, irreverent novel, a coming-of-age chronicle of one Barun Roy, a 'Bongo' lad from a well-off family (Ma, Papa plus sister Sunam) growing up in Jodhpur Park in the Calcutta of the '70s, which means Naxals and police violence, Moyna-di the tenant's daughter on the third floor and eating prawn cocktail in the Mocambo on Free School Street. Barun then is sent to boarding school at Mayo College (which is actually a school, from class 4 to class 12, or HSC, by our count). There he's instantly nicknamed Brandy and meets his soulmates Fish (the school's champion swimmer, who is the victim of a domineering, Muslim-hating father), PT Shoe (a Rajput princeling who is obsessive about cleaning his gym shoes and going to America to check out gora chicks) and Porridge (who, yes, loves porridge). 'Mayo was a totally cool-breeze place, or maybe breeze, because when things were really cool-breeze it was more hep to just call it "breeze", and if they were more disco-breeze, like some Travolta-type chap or a place or a happening, then it would be "cat" but we could change things around because there was no grammar to it, just what we felt, you know, not like some bloody big, fat Wren and Martin book saying you cannot use this construction here and all that because the participle is giving you a ****ing headache.' The above paragraph should not lead the reader to think that Tinfish is merely about Anglicized Indian boys at play (though it is that, too)--Barun is, after all, a Bengali, and sharp social observation, with its attendant social conscience and comment, seems to come naturally to him and the book is loaded with satire directed at Indira Gandhi's imposition of Emergency, at politicians and various corruptions, at barriers of religion, class and caste as well as the seedy politics of the extended family. Barun has been sent to Mayo because Kolkata just doesn't make the grade anymore:

'Papa had taken me one day to see Presidency College on College Street, saying it was the grandest college in India, but the place had a sad feel to it, like it used to be a grand place once upon a time but now there was nobody to look after it. He had become depressed seeing some of the building crumbling, the broken windows, locked gates, and red flags of communists and Naxals painted on the walls and on any inch of space the rows of bookshops on College Street had left. So he took me across the College Square lake to a juice shop where we sat and drank green mango shorbot, which he said he used to drink when he was a college student, and while the taste of the green mango had remained the same everything else had changed. He looked glum and I wished we could go home, away from this depressing place.' In fact, India, and Kolkata and Ajmer (where Mayo College is situated), of a certain period is wonderfully drawn. And within it, so is the smaller, separate, self-confessedly elite universe of Indian boarding schools ('Planet Mayo'). The classes, the medley of teachers, 14-year-old-ennui, tonga rides, inter-house sports, crushes on Zeenat Aman and Katy Mirza, 'quick frigs in bogs,' Brit-laced schoolyard slang, all have been rendered so acutely that you feel that you've been there every step of the way. Sudeep Chakravarti is uber adept at conveying the textures of life at boarding schools for boys:

'Dipi opened the big jar of Tang for us and we scooped the powder into our mouths with the orange-coloured plastic spoon that came with the jar, letting the little granules burst on our tongues, and chewed contentedly, saliva melting the Tang powder and taking it down our gullets. It was so much more fun to eat Tang than drink Tang, you know?' Or those defining arguments that foreshadow later debates, for the child is father to the boy, and the boy to the man:

Porridge was slowly getting converted to PT Shoe's religion…going on about America along with PT Shoe even if it was after seeing A Few Dollars More, which was about America in the old days when cowboys swaggered around walking bowlegged with all that riding and bathed in small tubs while some curly-haired babe from the saloon would wash the guy with soap and the bugger would sit in a tin tub with his own muck floating about him, the bloody jungli. 'Bastards,' I had told both of them one day, while Fish grinned, 'you'll be filthy all your life if you bathe in a tub.' 'What do you know? You've never been abroad,' Porridge shot back. 'I've talked to Bull and he says America is a very breeze place, you can buy nice things and do what you want and you don't have to clean airports like some Indian buggers do in London and all.' They didn't like it at all when I said I wasn't going to arse-lick any gora…while Fish laughed like a maniac because he was the only one among us who had travelled all over the world, even going to London to take flights to Nairobi when he was younger and sometimes going to Hong Kong before going to Sing. For all his flying about his planes, all Fish wanted was to fly free like a bird…so Fish kept saying it didn't matter where you lived or travelled because what mattered was doing what you wanted to do. But all is not breeze since nothing lasts, especially boyhood, which hath all too short a lease. There's growing up to be done. Midway through the book Barun's mother dies, to be followed by one of his buddies. And it is here that Sudeep Chakravarty's gifts as a writer are noticeable: deaths, disillusionment, maturity, a deepening of the self, the change from boy to no-longer-a-boy are seen not just in the plot, but felt by the reader in the prose itself, in the changes of cadence, from the previous child-like gush and flow to something a little more crisp and harder, to small variations of register and idiom, of slang and even line length. Adolescent shifts of moods and voices can be hard to capture in first-person narratives, but here it has been done masterfully, so that the gear changes are hardly felt at all--an enviable display of control over form and subject matter. The book ends with a farewell party to the outgoing class 10, of two hours of 'heaven and hell,' with Samira and a raging heartache. It would be unfair to give any more away. At the end, all I want to say is that the unconnected, isolated passages printed above hardly do justice to the book. It should be read whole, in one extended go, as I did, for the Tang to really burst in the reader's mouth. Khademul Islam is literary editor, The Daily Star.

|

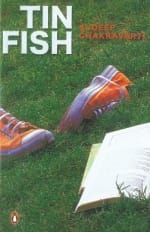

Tin Fish by Sudeep Chakravarti; New Delhi: Penguin India; 2005; pp. 236+ii; Rs. 250 |