BookReview

‘...merely fluid prejudice.’

Rebecca Sultana

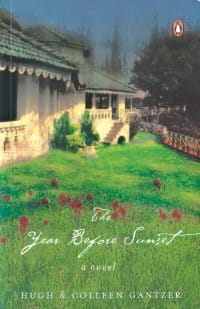

The Year Before Sunset: A Novel (pb) by Hugh & Colleen Gantzer; PenguinIndia, New Delhi; 2005; pp. 250; Rs. 250.On the eve of departure of the British from India, the Anglo-Indians found themselves in an invidious situation - caught between the European attitude of superiority towards Indian and Anglo-Indian alike and the Indian mistrust of them, due to their aloofness and their Western-oriented culture. The Year Before Sunset is a coming-of-age novel of an Anglo-Indian boy, Phillip Brandon, during the troubled days before partition. The novel starts with a question nobody seems to answer to Phillip's satisfaction and ends, after a series of adventures and suspense, with it still unanswered, but Phillip being, nevertheless, a bit wiser. Hindsight is always 20/20 and we can look at the mistakes of the past with insights lacking then, and so do the writers. The profound observations that a sixteen-year-old makes about inter-communal or inter-religious harmony sounds Utopian and rather anachronistic if we remember that the novel is set a year prior to the Partition, a time rife with angry emotions, divided loyalties and outbursts of violence all over India. Considering that India was reeling from communal violence the setting of the novel, the small Himalayan town of Lakhbagan with its sprawling bungalows, is blissfully protected from all that and presents itself as a picture of harmony and peace where everybody is aware of one's place and everybody is firmly entrenched in that place so that the social equilibrium is not disturbed. With hindsight now, we know at what cost such a picture perfect world was created. In its unquestioning acceptance of colonialism, the novel positions the audience in the spectator’s seat of the colonizer. Historical fiction and films of the Raj have given us enough glimpses into the lives in bungalows complete with numerous servants, each with a different duty. These big houses were Indian versions of English country estates and were ideals sought for by many English, few of whom could have ever achieved something so ambitious back in England. Even into the 1940s many of the houses would not have electricity, refrigeration, and would be infested with rats, snakes and even small animals. In Lakhbagan, the small community of the English, nonetheless, deliberately keeps modernization at bay so that the "newfangled inventions" do not change their peaceful life. Of course, that the novel is from the perspective of a young Anglo-Indian boy gives it a particular angle. With all his proclamations of his being an "Indian" Phillip does have his moments of hauteur as he dances with his mother and sees the shocked glances of his servants: "Too bad. This is our way of life and anyone who didn't like it could lump it" (174). Also the fact that he was studying in a boarding school where scions of maharajas and princes boarded as well could have clouded his vision. What gave rise to my initial confusion was the absolute colour-blindedness in Philip's descriptions of his schoolmates or of the people at Lakhbagan. There is no way of knowing whether the person being talked about is a white or a native. Surely, if I know my history right, caste, regional affiliation, linguistic distinction and religion did play a big part in one's identity formation or in influencing one's attitude towards the other. The only person who seems to be the one to make a big do over these differences is the arch villain, Pratap Chowdhury. More about him later. The Brandons, being Anglo-Indians, are never seen to be too concerned about their own positions in their hill town of Ringali. Yet history denotes experiences of racial tensions to rise out of a system where racial delineations are given primary importance and where the economics of employment, social status, geography of residence and access, are bestowed upon some and denied to others. In the novel, if there are hints of prejudice then those are based not on one's family lineage but rather on one's profession. Reading Gantzer one is unaware of tensions between the natives, the whites and the Anglo-Indians, whereas literary works abound that reveal the complexities as such. For example, Michael Korda's Queenie reveals the stereotypes that a young Anglo-Indian girl has to endure. But then, if Phillip is colour blind, he cannot be blamed for that. Schools, such as the one Phillip attended, was patterned on the British public school system and were attended by the children of the civil and military officers of the Raj. There they were taught from age seven to nineteen "the sterling virtues of teamwork, fair play and the great civilizing mission of 'the empire on Which the Sun Never Sets'" (3). While the strategy of divide and rule was used most effectively, an important aspect of British rule in India was the psychological indoctrination of an elite layer within Indian society who was artfully tutored into becoming model British subjects. This English-educated layer of Indian society was craftily encouraged in absorbing values and notions about themselves and their land of birth that would be conducive to the British occupation on India, and furthering goals of exploiting its wealth and labour, as Macaulay's infamous Minutes of 1835 revealed. Britain needed a class of intellectuals meek and docile in their attitude towards the British, but full of disdain towards their fellow citizens. The British were seen to be the harbingers of modernity and everything that was rational and scientific. These and other such ideas were repeatedly filled in the minds of the young Indians who received instructions in these schools. Phillips' schoolmates fall within this category. Even their names sound allegorical with a mixture of English and Indian nomenclature. We have Rags Singh and Buster Ahmed. The boys have a soaring ambition to attain--to become an ICS officer, that bastion of the Civil Service. It is no wonder then, that these idealistic young boys, protected as they were within the confines of their English schools, were unaware of the troubled times brewing. There were many, however, who did not find these values as preached by the British as ideals. One of these was Pratap Chowdhury. The whole novel, as we come to the end, is an elaborate plot to bring an end to an unruly revolutionary, Pratap Chowdhury, who would rather chant Quit India and Jai Hind and throw bombs than be patient enough to wait for the division of India as the British seemed fit to hand it over to the very British Nehru and Jinnah. Organized political resistance to the British occupation of India was mounting in the early part of the 20th century, yet the only evidence of this in the novel are rumors of a non-existent Rob Royish kind of character and petty revolutionaries who are dismissed as common trouble- makers. If he were not depicted in the usual villainous garb, a disgruntled young man angry at being denied the family title that went to his uncle (who, by the way, is a friend of the Brandons), Chowdhury would have been the ideal freedom leader in the likes of Khudi Ram, Bhagat Singh, Mangal Pandey or Titumir. But let's not forget who's telling the story. Perspective is, then, of utmost importance. As Mark Twain had said: "The very ink with which all history is written is merely fluid prejudice." One's man's hero can be another man's villain. Hugh and Colleen Gantzer, seventh- and second-generation Anglo-Indians, are more known as travel writers, photographers and makers of travel documentaries. They have also written on environmental issues. The book is a good read as an adolescent adventure. Rebecca Sultana taught English at East-West University, Dhaka. She will be leaving soon for Canada.

|

|