Introducing South Asian Poetry in English: Toru Dutt

Kaiser Haq

At least one eyebrow was raised at my characterization of Toru Dutt (4 March 1856-30 August 1977) as a genius in the previous article in this series I can well appreciate such skepticism, for our lexical currency has suffered worse inflation than our humble monetary unit. It is a common experience to find diverse personages, from rote-learning schoolboys to pompous mediocrities, being touted as geniuses. So let me make it absolutely clear on what sort of achievement I have based my claim.A Bengali girl born in Kolkata in the heyday of Empire masters French and English and acquires a fair amount of German, Latin and Sanskrit as well, and before being snuffed out by consumption at the age of twenty-one, produces the following: an anthology of English translations of 165 nineteenth century French poems, A Sheaf Gathered in French Fields (1876); a complete novel in French, Le Journal de Mademoiselle d'Arvers (Paris: Didier 1879); a collection of poems derived mainly from Sanskrit sources, Ancient Ballads and Legends of Hindustan (London: Kegan Paul 1882); an incomplete English novel, Bianca; a few translations from the French sonnets of the Comte de Gramont; a few critical essays (published in the Bengal Magazine). Critics like Edmund Gosse and E. J. Thompson enthusiastically receive the English verse collections, and eminent French men of letters wax eloquent over the French novel. Some of the greatest names in literature are invoked to indicate both the precocity and potential of Toru Dutt. E. J. Thompson declares her "one of the most astonishing women that ever lived, a woman whose place is with Sappho and Emily Brontë, fiery and unconquerable of soul as they." The Saturday Review (London, August 23, 1879) avers: "Toru Dutt was one of the most remarkable women that ever lived. Had George Sand or George Eliot died at the age of twenty-one, they would certainly not have left behind them any proof of application or of originality superior to those bequeathed us by Toru Dutt; and we discover little of merely ephemeral precocity in the attainments of this singular girl." And Gosse, introducing Ballads of Hindustan, notes that "Within the brief space of four years which now divides us from the date of her decease, her genius has been revealed to the world under many phases, and has been recogonized throughout France and England." I might well highlight the word "genius" above and exclaim, Quod erat demonstrandum! But I am aware that modern sceptics are scornful of the effusions of eminent Victorians. It will be pertinent therefore to cite modern opinion. Leading contemporary (i.e., post-Partition) Indian English poets have been generally dismissive of their predecessors, except for Toru Dutt. The poet Parthasarathy, for instance, in introducing his anthology, Ten Twentieth Century Indian Poets, singles out Toru, from among the entire tribe of nineteenth century anglophone versifiers, as 'the only one who had talent,' and with 'an undisputed claim to be regarded as the first Indian poet in English.' Rosinka Chaudhuri, who has recently published the most comprehensive critical study of the subject, Gentlemen Poets in Colonial Bengal: Emergent Nationalism and the Orientalist Project (Calcutta: Seagull Books, 2002), rightly credits her with having transcended the rigid Orientalist conventions that straitjacket her predecessors, "as the language she uses transforms the mythological content in her poems with their individual, and essentially modern, voice. Her modernism is evident from the way the mythological content of her poems does not remain extrinsic to her work as in the case of her predecessors, but is internalized in a consciousness that she both invokes and interrogates as she creates her own style." Thus, in "Savitri," the mythic past is contrasted with a degenerate present: "In hose far-off primeval days/ Fair India's daughters were not pent/ In closed/ zenanas." Feminist critics like Susia Tharu have shown that Savitri is one of a series depicted by late nineteenth century Indian poets (Sarojini Naidu and Aurobindo Ghose were prominent among the others) aimed at projective her as an Indian heroine par excellence, possessing a dual aspect--chaste Victorian on the one hand, and on the other a redeemer of her nation (personified in her hapless spouse Satyavan). More of a poetic advance is exemplified in "Sita," which instead of simply narrating the traditional tale focuses on the familial scene where it is retold by a mother to her three children. The whole poem is reprinted alongside so that readers may fully appreciate the charming drama of storytelling. A point worth adding--that Rosinka Chaudhuri seems to have missed--is the prosodic innovativeness of the poem. This aspect of Toru's verse was noted, albeit unappreciatively, by Gosse, who complained, apropos of the translations from French poetry, that "exquisite" as some of them are, at times "the rules of our prosody are absolutely ignored, and it is obvious that the Hindu poetess was chanting to herself a music that is discord in an English ear." Even the Ballads of Hindustan that Gosse considered "Toru's chief legacy to posterity" contained "much . . . that is rough and inchoate." To my postcolonial ear, what Gosse found discordant appears as an attempt--unconscious no doubt--to escape from the straitjacket of conventional metrics and find an Indian voice. "Sita" seems to be notably successful in this regard. Its twenty-two decasyllabic lines include only one regular iambic pentameter. Half the lines contain two or three variant feet. Of a total of 110 metrical feet, as I would scan then, seventy-five are iambs, eighteen are pyrrhic, ten trochaic and seven spondaic. The overall effect is a subtly cadenced poem in which the prosodic liberties taken are balanced by the formal control of a neat rhyme scheme. Toru's translations from French, unsurprisingly, show a fondness for the Romantic (Victor Hugo et al), but it is quite extraordinary that her taste is catholic enough to embrace such precursors of modernism as Gerard de Nuval and Theophile Gantier, and the father of modernism himself: the two poems of Baudelaire she has included must be among the earliest to be translated into English. The Victorian idiom she uses may read quaintly, but not so the notes she has appended to the volume; their crisp prose and tone of quiet authority will continue to impress readers. Witness the note on Baudelaire, which, curiously enough, makes an interesting critical point by referring to a poem other than the two she has translated: Sonnet.--The Broken Bell. Charles Baudelaire, the author of this sonnet, is a poet and critic of considerable eminence; but he borrows, without acknowledgment, too much from English and German sources. Look for instance at a little piece of his, entitled 'Le Guignon,' consisting of fourteen lines,--not put in the legitimate form of the sonnet. First you find the line, 'L'art est long et le temps est court.' Well! say, 'Art is long and time is fleeting' is a proverbial expression, and Baudelaire has as much right to use it as Longfellow, but then come the lines-- 'Mon cœur comme un tambour voilé

Va battant des marches funèbres.' Does not that remind one rather too strongly of Longfellow's 'And our hearts, tough true and brave,

Still like muffled drums are beating,

Funeral marches to the grave'? Still it turns to a question of dates. Both of them are living poets. Who wrote his lines first? But there is assuredly no question of dates, or question of any kind whatever, immediately after, when you find, 'Maint joyau dort enseveli

Dans les ténèbres et l'oublie

Bien loin des pioches et des sondes;

Mainte fleur épanche à regret,

Son parfum doux comme un secret,

Dans less solitudes profondes.' Can anybody render into French verse, more literally,

Gray's beautiful but hackneyed lines, 'Full many a gem of purest ray serene

The dark unfathom'd caves of ocean bear:

Full many a flower is born to blush unseen

And waste its sweetness on the desert air'? Charles Baudelaire died only a short time ago. Such finely controlled prose, from the pen of a nineteen-year-old is even more precocious than the verse translations. The external cause of such maturity was doubtless the Dutts' European sojourn, which had a tremendous educative influence on Toru and her elder sister Aru. In 1869, when the family set sail for Europe, the children had already received an excellent grounding in literature and music from private tutors as well as their parents. The Dutts stopped for several months at Nice where the two sisters went to school and fell in love with the French language. Then, after a long halt in Paris, they arrived in London in the spring of 1870. It was here that Toru began writing in earnest. Cousin Romesh Chunder Dutt, then in London to prepare for the civil service, recalled spending "many pleasant hours with my young cousins" and noted that "literary work and religious studies were still the sole occupation of Govin Chunder and his family." There was musical education too, as Toru's letters indicate--several hours daily on the piano plus singing lessons to develop their clear contralto voices" (Dutt père's description). Their social life was busy too, and even productive of the kind of anecdote that acquires literary value. Lord Lawrence, who had lately been Viceroy in India, called on them and finding Aru reading a novel commented chidingly, "Ah! you should not read novels too much, you should read histories." Toru replied for her sister: "We like to read novels." Lord Lawrence exclaimed, "Why!" Whereupon Toru smilingly aphorized with a paradox worthy of Wilde, "Because novels are true, and histories are false." The swift collapse of the French in the war with Prussia was distressing to the Dutts, especially to Toru, who was provoked into a poetic protest in "1870", subsequently included among the miscellanies concluding the Ballads of Hindustan: "Not dead,--oh no,--she cannot die!/ Only a swoon, from loss of blood!" Her indignation didn't spare England either: "Levite England passe her bys/ Help, Samaritan! None is nigh." The following year the Dutts went to Cambridge where Toru and Aru attended "the Higher Lectures for Women," which helped them work on perfecting their French. In the summer of 1872 Toru met Miss Martin, a clergyman's daughter, who became her closest English friend, and when the Dutts returned to Kolkata in September 1873, Toru corresponded with her regularly and copiously. Toru's letters have survived and account for 232 pages of the Life and Letters of Toru Dutt, lovingly compiled by Harihar Das and published in 1921 by Oxford University Press. Together with the other letters in the book, they are an engaging record of the author's life and times. They are not only indispensable to the student of cultural history, but possess as much literary merit as the writer's poetry and fiction. Indeed, the letters give an insight into the complexity of Toru's situation much more graphically than do her purely literary works. On the one had she firmly affirmed, "India is my patrie", and frankly described the inhumane aspects of colonial rule; on the other, finding life in India too constricting (she notes sadly that on her walks in the Dutts' country house at Baugmaree it would be improper for her to step beyond the boundaries of their property) she longs to return to Europe. The Dutts in fact would have returned, but for the twin tragedies that overwhelmed them. The four years that remained of Toru's life were as intense as one can imagine, marked by bereavement, mortal illness, assiduous study and phenomenal creativity. In July 1874, Aru died of tuberculosis, leaving behind translations of eight French poems that her sister incorporated into Sheaf Gleaned in French Fields (1876). No sooner had this book appeared than the signs of the disease showed in Toru as well. It ran its characteristic up and down course through which Toru heroically and optimistically continued her scholarly and creative pursuits. Soon after the return to India Toru, under her father's supervision, had begun the study of Sanskrit, the creative fallout of which began to appear in periodicals and were subsequently collected in Ballads of Hindustan. Only months before her death she came across a French book, La Femme dans l'Inde Antique ("Women in Ancient India") and wrote enthusiastically to its author, Clarisse Bader, offering to translate it into English. Permission to do so was granted at once, but Toru's declining health wouldn't allow her even to start the work. The correspondence between the two writers, however, evinces growing friendship, and when Toru's French novel was discovered and published after her death, it was prefaced by a warm tribute from her French pen friend. The novel has been made available for the first time to the common anglophone reader in a new translation titled Diary of Mademoiselle d'Arvers (Penguin India 2005), which should be noticed separately. Kaiser Huq teaches English at Dhaka University.

|

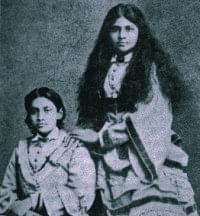

Aru Dutt and Toru Dutt (1872) |