Book Review

'neither from here nor from there’

Rubaiyat Khan

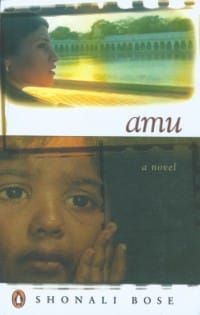

Amu, Shonali Bose; Penguin India; 2004; 142 pp.; Rs. 200.'Amu', a short novel by film-maker Shonali Bose, is based on the life of a twenty-one year old Indian-American woman named Kajori Roy, orphaned during the 1984 Sikh riots in Delhi. It is the story of a rather convoluted journey she undertakes in search of her roots when she returns to India--the land where she was born, and where she'd lost her birth parents. The novel is based on Bose's feature film, entitled the same. Kajori, or rather Kaju, is clearly the central character, though a collage of the lives of a host of other characters is presented alongside her story. Keya Roy, Kaju's foster mother and a social activist, moves to L.A. with three-year-old Kaju in an attempt to erase the horrific events of the genocide that had had a traumatic effect on the young girl who'd witnessed both her parent's deaths. Bose attempts to portray a degree of closeness within the mother-daughter relationship, but one that inevitably falls short, as she fails to add any real depth to it. The only complexity in the relationship arises out of the fact that Keya's deep-seated insecurity of losing her daughter prevents her from disclosing the truth of Kaju's past to her. Both women are meant to be seen as suffering a great deal from internal conflicts. Kaju's return to the land which she'd felt was a part of her, only serves to alienate her. The intensity of the Indian landscape, its class distinctions and poverty-stricken masses, the infringement on her independence to move around freely as a woman, coupled with flashes of the bloodbath from her past overwhelms her, and Kaju realizes soon enough--and as the author not so eloquently puts it--that she is "neither from here nor from there". She is neither an American, nor is she an Indian. Keya suffers from another kind of disillusionment. Both lands she calls home have their individual set of disappointments. She however, unlike Kaju, blends right in with her old surroundings when she returns, and is able to instantaneously reconnect with ‘familiar’ sights and sounds. This concretizes the notion of India being her real homeland, and where her identity stems from, even though she has built a life in America. Kaju, on the other hand, is more like driftwood, unable to neither absorb nor reconcile. Bose does create a commendable, stylistic touch by making her central character film--in fragmented parts--the Indian landscape, in an attempt to decipher and to piece together all that is around her; it also allows for a certain degree of emotional detachment from the intensity of her experiences, which otherwise threatens to engulf her completely. What is unbearable however is the overall sense of apathy and disconnectedness one might feel while reading the book. It certainly does not draw the reader in with its vapid, lifeless prose; in fact, the novel reads like a screenplay, and does a poor job of depicting what may otherwise have been a good film. What we, as viewers may have been able to glean from watching 'Amu', the film, Bose puts a damper on with a mere telling of events within the novel, and simply regurgitating what was shown on screen. For instance, while reading the book, you can actually envision some wonderful details which could make for some poignant moments on screen, but within the novel's scheme, it appears to have been unnecessarily lingered upon, let alone even observed to begin with. (Eg. "Kaju stood in front of the mirror and splashed water on her face, and resolutely lifted her chin," or, "Alone, in his book-lined study, Arun put his head in his hands," and so on.) The reader is, somewhat insultingly, spoon-fed as well. For example, we are 'told' that Kaju uses her camera ‘not just as an extension of herself, but as a way to meet the gap between herself and the alien situations she encountered’. There is almost no room for the reader to figure it out on his/her own, or extract anything further out of the metaphoric gesture of filming. The prose overall solidifies the notion that Bose, perhaps a good director ('perhaps', because this reader has not had a chance to watch 'Amu', the film), falls short as an author. Bose merely skims the surface of more complex issues, whether it is the turmoil caused by the genocide of 1984, a quest to find one's identity, or class discrimination in India. Therefore, it turns out to be a rather chaotic display without any real focusing on one particular issue. A final word of advice would be to watch the film rather than read the novel, as the former is possibly more layered and well executed. 'Amu' may well establish Shonali Bose as a good director, but she does not deserve any particular accolade as a writer. Rubaiyat Khan is a feature writer for The Daily Star.

|

|